From the classrooms of Harvard Business School to boardrooms across America, Dennis Kozlowski was long hailed as a corporate savant. Then, almost overnight, he became America’s poster child for greed, avarice and financial gluttony. As CEO of Tyco International, Kozlowski transformed a small obscure company into a wildly successful, multi-national conglomerate.

But perhaps equally spectacular as the rise of Tyco itself is the story of how a confluence of events led to the prosecution of the person who created this legitimate and enduring enterprise. The case that ultimately brought down Kozlowski raises troubling questions about how our legal system may have delivered a gross injustice to an individual who was guilty more of bad optics rather than criminal behavior.

Leo Dennis Kozlowski was raised in a three-family cold-water flat in a poor neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey, and his upbringing was anything but lavish. The son of a policeman, Kozlowski worked his way through Seton Hall and ultimately landed a job at a small industrial company in New Hampshire called Tyco International, which manufactured fire alarms and heating valves. Over a twenty-five-year period, Kozlowski methodically worked his way through the ranks, becoming chief operating officer and ultimately CEO.

Leo Dennis Kozlowski was raised in a three-family cold-water flat in a poor neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey, and his upbringing was anything but lavish. The son of a policeman, Kozlowski worked his way through Seton Hall and ultimately landed a job at a small industrial company in New Hampshire called Tyco International, which manufactured fire alarms and heating valves. Over a twenty-five-year period, Kozlowski methodically worked his way through the ranks, becoming chief operating officer and ultimately CEO.

The company’s success under Kozlowski’s leadership was nothing short of stunning. He took the company from $20 million in sales to $40 billion and built a conglomerate whose market cap exceeded Ford, GM and Chrysler combined. At one point, he was the highest paid CEO in America and his face graced the cover of virtually every major business magazine in the country.

If ever there were a perfect storm that could have sunk the career of an enormously successful and talented corporate icon, Kozlowski managed to find it and sailed directly into the eye of the hurricane. At the time, fraudulent business activities being perpetrated by companies like Enron, WorldCom and Global Crossing were front and center, and the media, which had previously glorified the success of many business leaders, turned into prosecutors of anyone who appeared to be profiteering at the expense of the American public.

Kozlowski’s widely publicized and nearly comic excesses through Tyco included his purchase of a $6,000 shower curtain and a multimillion-dollar birthday party in Sardinia. He became caught in the crosshairs of Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who was running for reelection at the time. Kozlowski appeared to become a target to serve as an example to the would-be abusers of the system regarding the pitfalls of unethical business behavior.

Even before his trial on a litany of charges, many of which were questionable, Kozlowski was convicted in the court of public opinion. Having already given up the bulk of his fortune in unprecedented fines, Kozlowski paid the price of losing his freedom for the next seven years as well as his reputation. The stories and videos detailing Kozlowski’s lavish spending were used to influence jurors and may have had a material effect on their guilty verdict, which at one point led to Kozlowski spending nearly a year in solitary confinement in a state prison.

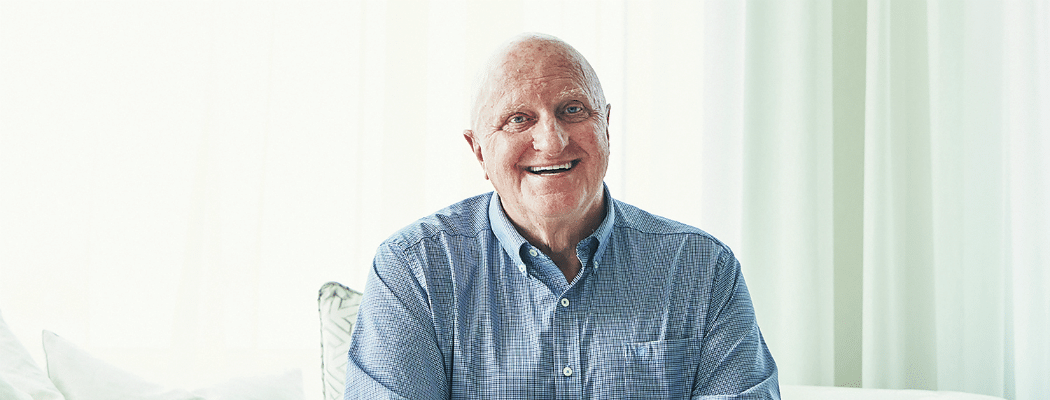

By his own admission, Kozlowski made mistakes both stylistically and otherwise. A closer examination of the facts suggests that bad optics and the goals of the prosecution may have superseded the inherent tenet of the American justice system to provide an impartial trial. For a man who created enormous and enduring wealth for Tyco’s stockholders, Kozlowski’s fall from grace was legendary. N Magazine sat down with Kozlowski to talk about the experience, his passion for helping people unfairly convicted of crimes and his deep connection to Nantucket.

N MAGAZINE: How did you first start coming to Nantucket?

KOZLOWSKI: In the mid-seventies, I went out there with some friends. I had a co-worker who had a home on Nantucket. I enjoyed everything about Nantucket. The sense of community. The feeling of being away from things while still having this vibrant group living there. I took every opportunity to go back out to Nantucket. I was drawn to the island in a big way. In the early nineties, I built a house out there.

N MAGAZINE: You had modest beginnings, commuting from a small town in New Hampshire in a Volkswagen Beetle. What made you the ambitious person you were, and I presume still are?

KOZLOWSKI: I didn’t set out to become a person who built $150 billion of value. It just never occurred to me. But each step along the way, I saw opportunity. Each step along the way, I had the ambition to achieve more than my predecessor did. And then once you hired your people that are a reflection of your own thinking, growth starts growing exponentially. The team that we put together was the driving force of what we did at Tyco.

N MAGAZINE: Did you have mentors early on?

KOZLOWSKI: My most significant mentor was a high school teacher who put me on the school debate team and worked with me a lot to be a straight-forward, logical thinker. In high school, I also worked in the pharmacy in North New Jersey where there was pharmacist who encouraged me to be more ambitious.

N MAGAZINE: You first joined Tyco in 1975. The company had revenues of about $20 million. When you left, the revenues were $40 billion. Was the dramatic growth part of your initial vision, or did the expansion just kind of happen organically?

KOZLOWSKI: The first thing I did was put together a team of really good people. That team was able to accelerate growth faster than anybody thought possible. Our stock was selling at high multiples. This gave us the ability to sell or use stocks to buy other companies.

N MAGAZINE: It was once said you were married to Tyco. Was this type of devotion the key to your success, and did it also create a distortion for you as to your view of the company and whether you felt it was your company?

KOZLOWSKI: Absolutely. When you spend as much time with the company as I did, you don’t know if you’re Tyco when you wake up in the morning or if you’re Dennis.

N MAGAZINE: There was an evolution of Dennis Kozlowski, from a person of simple beginnings with limited exposure to then having all the trappings of success. As someone who became viewed as one of the most admired CEOs in the world, did you feel yourself becoming a different person?

KOZLOWSKI: I never felt that I was morphing into someone else. I always had the same view of who I was: a poor kid who got out of the tenements of Newark, New Jersey. What did happen is that I wanted to show my success. So I acquired some homes, a boat and things that I had little time to use. I was probably on [my sailing yacht] Endeavour ten nights a year. I was probably at my ski house in Bachelor Gulch maybe five or six nights a year over the holidays. So I don’t know the exact numbers, but I never used any of these assets when I acquired them.

N MAGAZINE: So they were trophies?

KOZLOWSKI: Strictly trophies. And trophies that I didn’t need, but it was kind of my way of keeping score.

N MAGAZINE: When you appeared on the covers of Business Week, The Wall Street Journal, Fortune and other business publications, did you feel that you were breeding jealousy among your peers or among people in the media who tend to want to knock people off when they’re at the top of their game?

N MAGAZINE: When you appeared on the covers of Business Week, The Wall Street Journal, Fortune and other business publications, did you feel that you were breeding jealousy among your peers or among people in the media who tend to want to knock people off when they’re at the top of their game?

KOZLOWSKI: There’s no doubt about it. Not only people in the media, but a few people on my board, also.

N MAGAZINE: For nearly twenty-seven years, the company grew exponentially. Seldom do people go after those who enrich them, but in your case, the board came out with steak knives. During your years at Tyco, you were both CEO and chairman. Did that type of control play into what many thought was your over-reaching in compensation?

KOZLOWSKI: You can debate chairman and CEO as one and the same forever. I could give perfectly good examples of where it works and when it doesn’t work. But chairman and CEO had nothing to do with my compensation. We had a separate compensation board—the compensation committee—who set the compensation. We had a senior executive, the head of human resources, who met with the compensation committee without me present. I did not attend compensation committee meetings. I never once calculated my own bonuses. Our finance group did the calculation, and the deal was that our outside auditors had to sign off on the compensation before I was paid.

The amount of my compensation was a $1 million base. The remainder was variable and at risk. I was paid in stock by how well the company’s earnings were. I owned stock like any other shareholder. I had to achieve certain milestones to be paid cash bonuses. As I met those milestones, typically our earnings went up and the stock went up. The stock doubled a few times over a number of years. Any- body that invested alongside of me was going to earn the exact same amount of money.

N MAGAZINE: In the terms of your compensation, you were to receive a full $112 million golden parachute and you were granted 800,000 shares of the stock. The board obviously supported this compensation. But by most objective standards, even now, that was a huge payday. Was this just presented to you? Or did you negotiate it?

KOZLOWSKI: I reached a point where I started to do well at Tyco. We completed a number of acquisitions, things were moving along and I thought it was time for me to go do something else. I was dealing with a number of private equity companies at the time. I went to the Tyco board and said, “I’ve been around here for over twenty years and it is really time to pass the baton.” The compensation committee got together and came back and said, “We really want you to stay. We’ll give you three times your salary, stock and unlimited use of an airplane, an apartment and staff to take care of all this for the rest of your life.”

KOZLOWSKI: I reached a point where I started to do well at Tyco. We completed a number of acquisitions, things were moving along and I thought it was time for me to go do something else. I was dealing with a number of private equity companies at the time. I went to the Tyco board and said, “I’ve been around here for over twenty years and it is really time to pass the baton.” The compensation committee got together and came back and said, “We really want you to stay. We’ll give you three times your salary, stock and unlimited use of an airplane, an apartment and staff to take care of all this for the rest of your life.”

So I went to our vice president of HR, and said, “The board offer is probably worth over $100 million dollars. Please go back to the board and tell them I want three times my annual compensation of the stock, the bonus and the salary.” I thought there was no way in hell that they would ever support that. To my surprise, they approved it. I thought that was bizarre but I was feeling like a pitcher for one of the top major league teams. I’m thirty-eight years old, my arm is wearing out, so now they give me this huge contract.

N MAGAZINE: So this was the true golden handcuffs.

KOZLOWSKI: This was the true golden handcuffs.

N MAGAZINE: Did it occur to you that it might come back and bite you?

KOZLOWSKI: I did not know it was going to destroy me. I was 100 percent certain that there would be a lot of criticism. But at the same time, we’ve created so much value that I rationalized the compensation.

N MAGAZINE: Did you lose sight of the fact that this was not your company, that it was a shareholder-owned public enterprise?

KOZLOWSKI: It was the ultimate retirement package. I don’t know how it compares to other CEOs, but we did use General Electric’s proxy as a template. Our numbers were bigger, but I’m not sure. As I said, I didn’t put this together; consultants put it together. But I was the one who said, “Let’s times everything by three—the stock and the cash bonuses and everything.” So did I feel guilty that it was a public company and it wasn’t my company? The answer to that was yes and no. These were heady times. CEOs were all being put on a pedestal. CNBC, Fox, Bloomberg and all these programs were fighting to have us on the air. It was a way different time than it is now.

KOZLOWSKI: It was the ultimate retirement package. I don’t know how it compares to other CEOs, but we did use General Electric’s proxy as a template. Our numbers were bigger, but I’m not sure. As I said, I didn’t put this together; consultants put it together. But I was the one who said, “Let’s times everything by three—the stock and the cash bonuses and everything.” So did I feel guilty that it was a public company and it wasn’t my company? The answer to that was yes and no. These were heady times. CEOs were all being put on a pedestal. CNBC, Fox, Bloomberg and all these programs were fighting to have us on the air. It was a way different time than it is now.

N MAGAZINE: With that in mind, if someone could be convicted of bad optics, you would be extremely vulnerable. There were a series of purchases you made at the pinnacle of your career that turned people’s perceptions of you. Let’s talk about something that’s also probably not wildly comfortable, but one of the most legendary events that maybe shaped people’s view of you and generated an inordinate amount of press was the fortieth birthday party in Sardinia.

KOZLOWSKI: The party was ridiculous. My daughters were there. Some Tyco directors were there. Some Nantucket friends were there with others. It was over the top. It was not tasteful at all. Other people put the party together and I was not involved. However, I did personally pay the cost of the party.

N MAGAZINE: In the same realm of unfortunate optics, there was the $6,000 shower curtain heard around the world. How much influence do you think the shower curtain and these other symbols had on the outcome of your case?

KOZLOWSKI: They had a significant influence because you could watch these poor juries sit there for four or five months listening about compensation committee meetings and audit committee meetings and return on investment calculations. Some of the jurors were either asleep or had their eyes glassing over. But when you can pop in things like a $6,000 shower curtain, which is more than a lot of people’s rent, the prosecution was able to identify me as a bad guy.

N MAGAZINE: In 2002, Global Crossing, WorldCom and Adelphia filed for bankruptcy. And they were charged with allegations of Enron-like accounting issues. The Wall Street Journal led the charge, suggesting that Tyco should somehow be included in this same group. Was this just bad reporting on behalf of a singular reporter at The Wall Street Journal?

KOZLOWSKI: Mark Maremont of The Wall Street Journal spent ten years trying to find something wrong with Tyco. Mark was a bit of an unusual guy. We would have board meetings on Bermuda because Tyco was based there. Mark would sit outside of meetings in an effort to speak to directors afterwards. Mark spent a fair amount of time looking for something wrong with Tyco. This seemed to be his personal ambition. There was nothing impartial about Mark Maremont.

In fact, Mark came to the trial a few times and he identified a juror that he said had a hand signal to the defendants. No one else in the courtroom saw that, but Mark published that in The Wall Street Journal. So here is a reporter trying to influence the outcome of a trial by attending the trial and printing something that he thought he saw at the trial that really no one else saw at the time.

N MAGAZINE: Why was the Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau so enthusiastic about this case? Why was he so aggressive in his pursuit of you?

KOZLOWSKI: At the time, the federal government was prosecuting Enron, WorldCom, Martha Stewart. It was a time when the stock market crashed in 1989/90 and people had lost money in the market. CEOs and companies had been put on pedestals. Morgenthau was running for reelection and he was facing his first real challenge at the time. He had been district attorney for many years. He wanted to show that he was going to prosecute white-collar crime as well as the day-to-day crimes of New York.

N MAGAZINE: In his zeal, can you cite specific instances where he either tested the limits of the law or went over them?

KOZLOWSKI: I never once met Morgenthau. I never saw him in the courtroom. Morgenthau had a big press conference when he indicted me, and then I never heard or saw from him again. I didn’t even meet him at the indictment.

N MAGAZINE: But was he pulling the strings from behind the curtain?

KOZLOWSKI: He had to be because he was heading up the DA’s office. But where I think my rights were violated was Tyco had an attorney named David Boies who was a big-time celebrity lawyer. He was the attorney that the United States government hired when they wanted to break up Microsoft. When Al Gore and Bush were battling it out for the votes in Florida to become president of the United States, Al Gore hired David Boies. David Boies was brought in by a couple of directors to investigate me. His job was to win. It wasn’t to find truth and justice. It was to win—as simple as that. He was paid to win, so I would not have to be paid my retention agreement, which was worth hundreds of millions of dollars to the company.

David Boies handed the case over to Morgenthau, but then David Boies, who was being paid to find me guilty as a prosecutor, was allowed to testify in front of the jury as if he was an employee of Tyco or as if he had some kind of objective opinion about the case. Once Boies testified, my constitutional rights were violated

N MAGAZINE: During the trial, it became apparent that a number of things you were accused of were not crimes at all. Instance after instance, you were charged with things that weren’t valid. How is it possible in our judicial system, and with I would presume, capable representation, that these things were able to happen?

N MAGAZINE: During the trial, it became apparent that a number of things you were accused of were not crimes at all. Instance after instance, you were charged with things that weren’t valid. How is it possible in our judicial system, and with I would presume, capable representation, that these things were able to happen?

KOZLOWSKI: The behind-the-scenes prosecutor, David Boies was extremely good with the media, extremely good in opinion-making, and he fed all the information from Tyco to the prosecutor in a record couple of months. I left the company in June, and I was not under any kind of investigation for any spending or any issues at all. I was indicted in September. A nor- mal prosecutor’s office takes years to do these kinds of things.

In my opinion, they were handed a case by David Boies because of my retention agreement. That $300 million agreement was now coming back to bite me. My retention agreement was strongly worded. It said that the only time Tyco would not have to pay that retention agreement was if I was found guilty of a felony that was materially injurious to Tyco. So a couple directors got together and said, “We gotta find material injuries to Tyco because it’s embarrassing to show up at our country clubs and say, ‘We’re gonna be paying this guy all this money.’”

I never once had one discussion with a single director or anybody in that company from the day that I left on a Sunday and was indicted on Monday on sales taxes. I was never allowed back in the company. I was never allowed back to my notes, my records, my information, my personal belongings. On that fine Monday, David took over and totally locked me out from the office. I was told that David Boies hired a PR firm to disparage me. Before that I was on the cover of business magazines doing well, and now it came time to bring me down. I was instructed by my lawyers not to speak to the media. Our first trial was a hung jury and it was ultimately declared a mistrial.

After the first trial, the DA offered we negotiated, we could get it down to one to two years of prison time with a small fine. None of that happened. We went back to trial. They were able to pick up on these issues—the shower curtain, the spending, the personal lifestyle—as opposed to the facts.

N MAGAZINE: When the sentence came down it was eight-and-a-half to twenty-five years?

KOZLOWSKI: Yes.

N MAGAZINE: And you paid restitution?

KOZLOWSKI: I was hit with two financial obligations. One was a $100 million fine to the Manhattan DA’s office. I was also hit with full restitution to Tyco for everything I was paid, which was about another $100 million.

N MAGAZINE: So when this came down, what on earth was going through your mind when this was delivered?

KOZLOWSKI: I was shocked and I felt that an appeal process would turn this around.

N MAGAZINE: What do you feel you were guilty of? Were you guilty of anything, legally?

KOZLOWSKI: If the board changed their mind about my compensation or felt that I was overpaid, there was a civil process that should have resolved this – certainly not a criminal process. But nobody ever came to me and asked me to give the money back or do anything.

N MAGAZINE: In the broad sense, what were you guilty of?

KOZLOWSKI: I did push the organization hard and we built up a large company from nothing very quickly. We went from infancy to adulthood without passing through adolescence. And in that process, we never built the infra- structure or the documentation that most companies have to support the kind of growth we had. We didn’t have the lawyers or financial people on staff to support the large businesses that we were running. I was guilty of not building a corporate staff that was comparable to the size of the organization we were running.

N MAGAZINE: So ultimately, when you were sentenced, you spent eight and a half months in a maximum security prison. You were hardly viewed as dangerous. What was the justification?

KOZLOWSKI: They just didn’t know what to do with me. I was a high-profile inmate at the time, and the concern was that one of the gang members would get some notoriety by taking me out. So that was what was explained to me. They said, “It’s for your own good, because you are high profile.” But at the same time, inmates are savvy people. They know everything that’s going on. So everybody would be looking for some kind of help while you’re there too, seeking money. So part of that justification, too, was to keep me from being taken advantage of.

N MAGAZINE: And did you ever develop relationships with any of the prisoners, so that you felt you were able to steer them in the right direction?

KOZLOWSKI: Absolutely. I taught some people to get their high school equivalency in prison. And some of the books, the things they had were pretty archaic. And my brother-in-law was a special education teacher in New Jersey, so I had him send in all kinds of books and things they use, so we were able to have some better materials for some of the guys to use when they went for their exams.

N MAGAZINE: Did they realize who was teaching them?

KOZLOWSKI: To some extent. Someone might be reading a business book and one of the cases would be the Dennis Kozlowski Tyco case, and someone would surprisingly say, “This is you!”

N MAGAZINE: Were there any positive experiences in prison?

N MAGAZINE: Were there any positive experiences in prison?

KOZLOWSKI: I had many visits. These visits included [my now wife] Kim, who became very supportive. We met most Saturdays and Sundays and got to know one another over those years. We concluded that the criminal justice system is pretty screwed up and decided to do something about it when we had the opportunity. I came out and got involved with the Fortune Society of New York, which I now chair. We help thousands of former inmates transition into society every year. Kim is president of the Women’s Prison Association, and her group spends most of their time finding alternatives to incarceration for women. We have a passion for criminal justice reform and advocacy.

N MAGAZINE: Do you have any other thoughts or reflections about this experience?

KOZLOWSKI: If a CEO devastated a company, employees would stay away from him. But I had over a hundred employees visit while I was in prison. These were my senior staff, my secretaries, people up and down the organization. To this day, this group has been extremely supportive. That friendship and support has meant the world to me. I feel bad about what happened and the way it happened, but I feel good about the lasting relationships.

N MAGAZINE: You’re going to be coming back to Nantucket?

KOZLOWSKI: Yes.

N MAGAZINE: Is there any feeling of trepidation?

KOZLOWSKI: It’s all very positive. The support from Nantucket has been overwhelming over the years. When the DA would not accept my money for bail, the people on Nantucket put up their homes, their boats, their businesses. Fortunately, it didn’t come to that, but they were right there for me. Absolutely right there. I will never forget that and I am forever grateful.