Summer resident Wayne Rogers is embarking on a whole new train of thought in American infrastructure.

Imagine traveling from Washington DC to the heart of New York City in an hour. Even by plane, with all the hassles of checking in, security and delays, making that journey in under three hours seems impossible. But longtime Nantucket summer resident Wayne Rogers believes it can be done, and he’s refusing to let anything derail him.

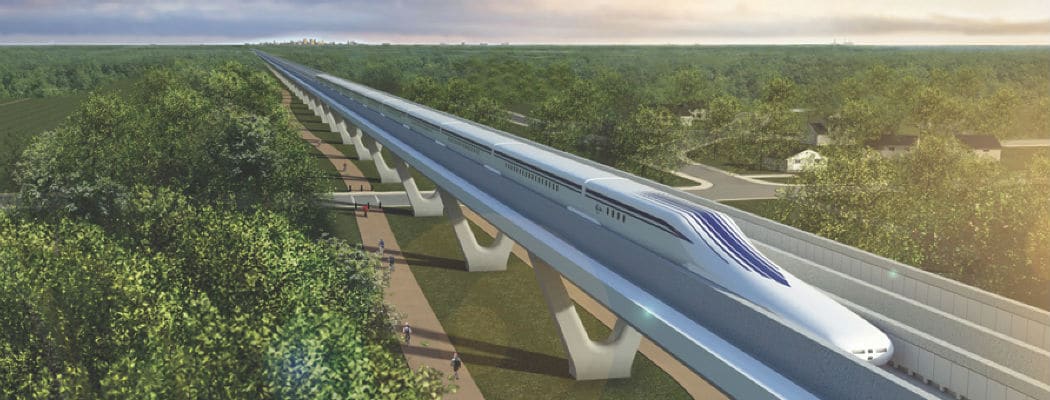

Hitting speeds of more than three hundred miles per hour, the Maglev (short for magnetic levitation) is a train that uses superconductive magnets to float over the track and accelerate and decelerate. The technology was developed in Japan, where super high-speed trains have been zipping hundreds of millions of people from city to city since the 1960s. In fact, these fifty-year-old Japanese trains move faster than the fastest trains in the United States today. The Maglev is more than twice as fast as Amtrak’s Acela. “Japan’s central railroad moves 150 million people a year on 100,000 trains,” Rogers says. “The average delay per year is thirty seconds, and they’ve never had a fatality.”

The idea to bring this high-speed rail to the Northeast Corridor hit Rogers five years ago when he received a call from a friend in the White House who worked closely with Japan. “He told me that Japanese executives really didn’t understand — having seen a vision of America where we’re a high-technology country, where every child has an iPhone, an iPad and laptops — why America hasn’t moved forward in newer technologies on their infrastructure,” Rogers remembers. “We think we’re leading the world in all our technologies, but somehow our infrastructure has been lost. We’re working on infrastructure that our parents and grandparents built.”

The idea to bring this high-speed rail to the Northeast Corridor hit Rogers five years ago when he received a call from a friend in the White House who worked closely with Japan. “He told me that Japanese executives really didn’t understand — having seen a vision of America where we’re a high-technology country, where every child has an iPhone, an iPad and laptops — why America hasn’t moved forward in newer technologies on their infrastructure,” Rogers remembers. “We think we’re leading the world in all our technologies, but somehow our infrastructure has been lost. We’re working on infrastructure that our parents and grandparents built.”

Focusing in on the Northeast Corridor, Rogers insists that the Maglev will transform the economy, the environment, and of course, transportation. Fifty million people live between Washington DC and Boston, and that number is projected to grow by another fifteen million by 2050. Yet of those 50 million, only 5 percent commute by train. As a result, traffic increased by 60 percent between 1990 and 2007, and congestion continues to worsen. According to Rogers, not only will the Maglev reduce traffic and emissions, but the high-speed train will effectively shrink the Northeast Corridor. “If you live in Baltimore, you could take a job in D.C. that pays 20 percent more,” Rogers reasons. “You would have 4.2 million more jobs within a one hour commute.”

The train will carry up to 750 people (twice as many as than the Acela) on a journey that Rogers claims is five times smoother than anything Amtrak has crisscrossing the country. “You can stand up and write your notes going three hundred miles an hour,” he says, having traveled in the test Maglev in Japan. “If you’ve ridden the Acela train, you’re lucky if you can bring your coffee back to your seat without spilling it—and that’s at eighty-six miles per hour most of the time.” The train’s magnetic forces prevent the possibility of derailments, while also consuming half the energy of a plane and emitting just a third of the CO2 missions. Considering all these positives, one might wonder why this project hasn’t left the station?

“You see the initial price tag to do the whole line from D.C. to New York, and it’s eye-popping,” Rogers says. The entire project is estimated to cost $100 billion, which has stopped many people in their tracks. But Rogers says connecting the Northeast Corridor can be accomplished section by section. “We’re going to do it in small chunks, the first phase will take you from Washington to Baltimore Airport to Baltimore, [which is] somewhere north of $10 billion.”

Once that section is in place, Rogers believes the scales will tip to proceed with the rest of the project and probably extend on to Boston. “When we talk about those type of sums of money, we forget that we spend $1 billion a week in the Middle East,” he says. “We could build out this whole first phase for ten weeks in the Middle East.”

Japan has already pledged $5 billion to get the project rolling, and while the Maglev is technically a private endeavor, Rogers hopes the federal government will play a role. To achieve speeds of 311 miles per hour, the Maglev needs to run on a mostly straight track, with very few turns. “A lot of this is going to be in a tunnel, which eliminates most of the problems of getting the right of way, but increases the cost,” Rogers says. “Now if you had the federal government participate in financing some of the tunnel costs, then you bring the overall cost of the project down [as well as] the ticket price.” Although the price per ticket is still far from being determined, Rogers thinks a ride will most likely cost between $1 to $2 a mile.

Japan has already pledged $5 billion to get the project rolling, and while the Maglev is technically a private endeavor, Rogers hopes the federal government will play a role. To achieve speeds of 311 miles per hour, the Maglev needs to run on a mostly straight track, with very few turns. “A lot of this is going to be in a tunnel, which eliminates most of the problems of getting the right of way, but increases the cost,” Rogers says. “Now if you had the federal government participate in financing some of the tunnel costs, then you bring the overall cost of the project down [as well as] the ticket price.” Although the price per ticket is still far from being determined, Rogers thinks a ride will most likely cost between $1 to $2 a mile.

The long-term objective is not to have these high-speed trains crisscrossing the country from coast to coast. Rather, the Maglev will focus on densely populated areas and work in harmony with airports, connecting them to city centers and offering alternatives when a flight is cancelled. “Once we integrate all these airports together, then you become one system,” he explains. So if your flight is cancelled in Philadelphia, you can take the train to Baltimore and jump on a different flight. Seventy percent of all air traffic delays, according to Rogers, emanate from around the Northeast Corridor.

More philosophically, Rogers looks at the Maglev in a historical context. “These are the kind of projects America used to do,” he says. “Our forefathers were so much more willing to take a leap on [projects like this.]” He points to President Abraham Lincoln starting the Continental Rail Road in the midst of the Civil War and John F. Kennedy pledging to put a man on the moon within a decade, even though the country didn’t have the rocket technology yet, as instances of the audacious American spirit that today appears to be lacking. “We have a train that already exists in Japan,” he says. “To bring it to the United States and deploy it — in the context of all those other [historic projects] — doesn’t seem to me to be such a hard pull.”

Rogers has a track record of being ahead of the curve. Before Maglev came on his radar, he made his career in the energy sector, building hydroelectric power plants and wind-powered facilities back when renewable energy was thought of as “some fringe fantasy.” Now he looks at the Maglev as possibly his final project, a legacy to leave behind. “I guess at this point in my life, there are few things that you can do that can really transform everything,” Rogers says. “I see this as a transformational project so that when I leave, I’ll have changed things around dramatically.”