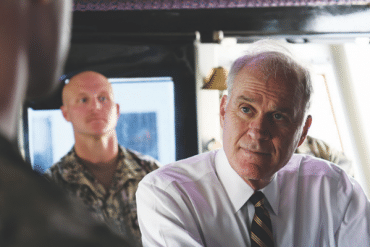

A conversation with Massachusetts State Representative Dylan Fernandes.

Four years ago, at the age of twenty-six, Dylan Fernandes became one of the youngest candidates ever elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. A fourth-generation resident of Falmouth, Fernandes now represents his hometown as well as Martha’s Vineyard, Elizabeth Island and Nantucket. N Magazine met with Fernandes during a recent visit to the island to discuss his rise in politics, his vision for the future and the issues he believes are most pressing to Nantucket.

You’re one of the youngest state reps in the country. How early did you start thinking about running for office?

Starting when I was around eighteen, I got involved in politics through interning and then eventually working as entry-level staff on campaigns. My first paid job in politics was when I was twenty-one when I took a semester off college and worked for Elizabeth Warren in the South Coast. I later became Maura Healey’s political director on her campaign for attorney general, and then I was working in civil rights and consumer protection in the attorney general’s office. I knew I wanted to work in government to help advance people’s lives, but I never plotted to run for this seat. When my predecessor Tim Madden announced that he was stepping down, I thought what better way to continue the work that I love doing and that I found meaningful and impactful than to do it for the communities where I grew up and love?

What issues are most important to you and the people you serve?

As a millennial, there’s no greater issue that’s going to impact my generation, or my children’s generation, than that of climate change. More than any other place in the commonwealth, this is a district that is going to be really negatively impacted by climate change. The housing crisis is another huge issue. It is profoundly unaffordable everywhere in the commonwealth, but particularly in the Cape and Islands for a young person out of college to be able to afford a home and to live in the community that they grew up in and love. I also came up in the midst of the opioid epidemic and have seen how that has really impacted my friends through high school. I’ve lost people to it. That’s another issue that is particular to the Cape and Islands. We have some of the highest rates in the state of opioid overdose deaths. So those are the three issues that I feel really passionately about and that align with the needs and cares of the people I represent.

You have a rare medical condition that has made you more sensitive to the health care issue. Do you want to expand on that?

I have an incredibly rare disease called fibro-adipose vascular anomaly. I basically had a foot-and-a-half-long tumor in my left thigh that was incredibly painful. I grew up being an athlete, playing four years of varsity sports, but as the tumor grew, I started having debilitating chronic pain. Doctors didn’t know what it was when I was growing up. I had actually been misdiagnosed twice and had procedures that did nothing. Then years later, I visited a doctor who was looking at this in a new light at Boston Children’s Hospital, and he made the discovery of a new disease and wrote a seminal paper and study on it. Treatment wasn’t an option because they had just discovered it. They later discovered that removing the tumor can be effective. I eventually got treatment and got it removed entirely and it just transformed my life. The experience made me realize how mentally and physically challenging it is for the millions of people living with chronic pain and how important it is to have really innovative health care in this state that helps us treat some of these very rare diseases.

You’ve worked for Elizabeth Warren and for Maura Healey and have strong, progressive credentials. The recent election in New York City of a pro law-and-order candidate has signaled to some people that certain progressive policies have gone too far and were responsible for New York’s decline. How can you be progressive and practical at the same time?

I can’t really speak to the New York race; I didn’t really follow it. But I can speak to what practical progressivism looks like. It’s different at different levels. In a municipal government and in a state government, you have to have a balanced budget. You can’t deficit spend like the federal government. So that constraint is going to force you to have practical solutions. Massachusetts is an example where you can advance progressive policies and still have a balanced budget that is responsible. We’ve done that every year while advancing some of the most progressive policies in the nation. We passed the largest climate bill in Massachusetts’ history, in our nation. Just a few months ago, we passed the Rowe Act, which was a big piece of legislation around codifying and protecting women’s rights and access to abortion in the state. We’re doing this as we’re passing balanced budgets. This year we’re going to have a surplus. So you can do both.

One of the reasons why Massachusetts is so effective at managing social issues is because we have a tremendous revenue stream. Our tax base, while smaller than many states in terms of people, is enormous because of the success of those people. There are policies and proposals on the horizon that a lot of business people are very concerned about, one of which is the millionaires tax. We’ve seen that similar tax policies in Connecticut that have gone after the high-end earners have been devastating to the state. Those same policies are responsible in part for the huge exodus out of New York City. What is your position on policies like a millionaires tax?

I’m very supportive of the millionaires tax and it’s widely supported in Massachusetts, according to the polling. It’s highly likely that this will pass and become law in the state. Massachusetts has its income tax baked into its constitution, and that makes it highly inflexible and really challenging to change. Everyone in Massachusetts pays the same percentage tax—but that 5 percent that the teacher is paying into the tax system is way more meaningful to her than someone making a million, $2 million or however many millions a year. It’s a profoundly unfair system. It’s quite regressive that everyone, no matter what their income is—whether they’re a firefighter or an investment banker making a boatload of money—is paying the exact percentage rate. That’s bad policy. When we see the millionaires tax, which is a meager 4 percent increase off of that 5 percent just on money over the first million dollars earned, that doesn’t seem like a massive change to me. It seems only fair that someone making multimillion dollars a year would pay a slightly higher percentage than someone making $40,000, $50,000, $60,000 a year.

However, the law of unintended consequences sometimes can come into play. Thirty thousand high-earning individuals in New York City left to go to Florida because of the tax status, then New York’s tax revenues dropped precipitously. Massachusetts is a breeding ground for wildly successful entrepreneurs who have produced everything from the COVID vaccine to advanced computing systems and products. How do you position the state so that it has a fair tax code but doesn’t punish success?

I would disagree that a 4 percent increase on incomes over a million dollars is a punishment. Massachusetts is an ideal place to live in and raise your children in because of the investments that the state makes. We have the number one education system in the country because the state has made significant investments in education. That makes us an ideal place to live and helps bolster our education economy, which is a huge attractor. But this stuff costs money. You’ve got to pay for it. Where is this money going to come from? It would be bad policy to ask poor middle-income people to pay more when they’re already struggling. It’s got to come from somewhere. I think it’s only equitable that it comes from the ultra, ultra wealthy.

It is hard to feel sympathy for the billionaire who pays nothing in income taxes, but even these people pay huge property taxes, payroll taxes, transactional taxes and are often very philanthropic. What are your thoughts on this?

I don’t disparage wealthy people at all. I think they’re fantastic contributors to our society, our economy. I want people to be as wealthy as they can be. The last thing we want to do is vilify anyone for the incredible success that they’ve had. I try to strike the balance here in saying that we are all part of the same small, tight-knit Massachusetts community that appreciates everyone, the wealthiest and the poorest. I think we should dispel the kind of punitive nature of the language around this debate. I’m a first-generation college student in my family. I grew up understanding that it takes a lot to start your own business and work to see it grow and that success can’t be punished. It needs to be supported here in the state.

You were involved with the Rappaport Institute at the Kennedy School of Government. Tell us a little bit about that and how it may have shaped or helped you in your pursuit of public office.

I received the Rappaport scholarship last year, so it didn’t really shape pursuing office, but it’s just an honor to get the scholarship. Jerry and Phyllis Rappaport have set up this incredible fund that supports emerging leaders. The state government is one of the best run in the country because the Rappaport Institute has been incredibly generous in supporting young and emerging leaders getting into government in advancing their education at Harvard and elsewhere. It has really created the pipeline that is necessary for people to get into public service and stay in public service. For me, it’s been a fantastic experience, taking courses in digital government and decision science, which has really informed my approach to policy making. It has shaped some of the legislation that we filed this past session.

What problems do you think are the most pressing for the island and are foremost on your radar screen?

What problems do you think are the most pressing for the island and are foremost on your radar screen?

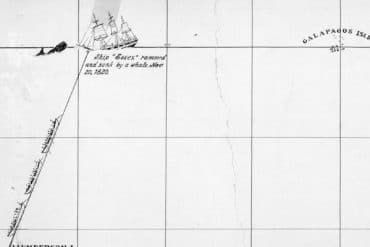

Probably more than any other place in the commonwealth, Nantucket is going to be deeply impacted by climate change and sea level rise. That’s not just losing part of the downtown and Brant Point, but it also has other impacts like increasing ocean acidification, which will deplete the shellfishing industry. The lack of affordability on Nantucket will erode the island at a far greater pace than the ocean ever will, if we can’t help people get the housing that they need. When I step on-island, that’s the issue I hear the most about. We’ve been really involved in the campaign around the housing bank for Nantucket and were involved in passing the short-term rental fee up here that will bring more money to the island.

At your age, with your attributes, you could have a long political runway. What are your ambitions beyond your current position? And do you see yourself in this business for a long time?

I got into this because I want to make a positive impact in people’s lives. I look at government as the most effective way to do that. But there are so many other ways. The private sector, the public sector—you can change the world in those sectors as well. I know I want to continue to make an impact throughout my life. I don’t think government is the only place to do that. I don’t know how long I’ll be in government for. Both my parents are small business owners, so entrepreneurship has always been something that’s been on my mind as well. But I love the work that I’m doing for Nantucket and the Vineyard and the Cape. So at least for the next two or three years, I’m not going anywhere.

This interview has been edited and condensed due to print space limitations.