Chris Matthews from Carter to the Kennedys.

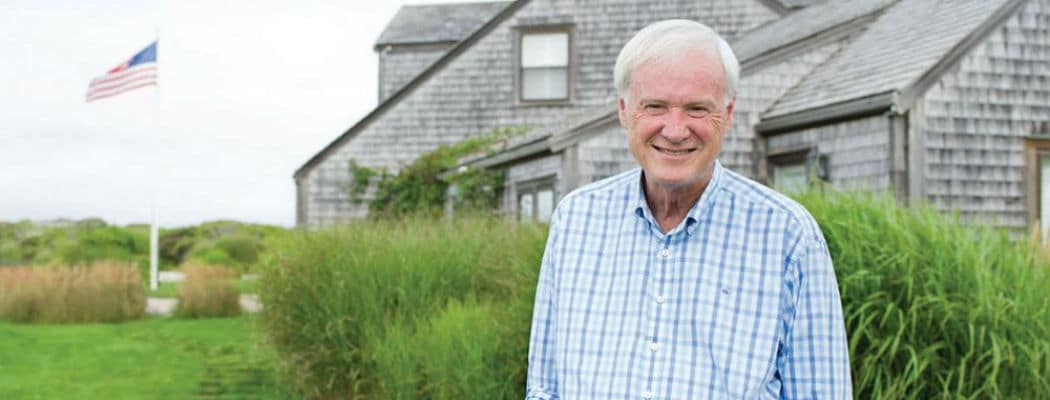

Chris Matthews is best known as the long-standing host of MSNBC’s Hardball where he has served as a political commentator for twenty-three years. His insight into politics dates back to when he was a speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter. Since entering the media, Matthews has become a prolific author of bestselling books that focus on the inner workings of politics and some of its most significant players. After years of research, Matthews is about to release his latest book, an in-depth and revealing profile of Bobby Kennedy, which comes nearly fifty years after his assassination. N Magazine sat down with Chris Matthews at his home on Nantucket to discuss his career, his passion for politics and his thoughts on the late Bobby Kennedy.

N MAGAZINE: You and your wife, Kathleen, have been coming to Nantucket for many years. How did you first discover the island?

N MAGAZINE: You and your wife, Kathleen, have been coming to Nantucket for many years. How did you first discover the island?

MATTHEWS: We had our honeymoon here in 1980. I didn’t have a ton of money. I was a speechwriter for President Carter and I got a house on Quince Street in town. I was basically living on the money they had paid me back for my rooms during the campaign. The money paid for the hotel rooms and the engagement ring. Then sometime in the 1990s, Suzanne and Bob [Wright] invited us up here for the Film Festival and we’ve been involved in that ever since.

N MAGAZINE: Where did your interest in politics first take root?

MATTHEWS: I remember [leaving] a movie theater in Philly, walking downtown with my dad in 1952, when I looked at a general getting off a plane. I said, “Is that guy president?” And he said, “No, but he will be.” I think [Eisenhower] was coming back from NATO or something like that, which would’ve been March in that year. I followed it all through the fifties and the 1960 campaign.

N MAGAZINE: What was your path to Washington?

MATTHEWS: I went to Holy Cross, which brought me up here again to Massachusetts. Then I went to graduate school in North Carolina. I got a free ride at North Carolina Chapel Hill. I went to Peace Corps in Africa. I was a trade development adviser in Africa for two years in Swaziland. I trekked around Africa by myself — my great adventures. Maybe that’s the next book: Two Years in Africa or something. I worked my way back through Israel for a month. Then I worked my way back through England. Then I worked my way home and got to the Hill.

N MAGAZINE: What was your first job on Capitol Hill?

MATTHEWS: I was a Capitol cop for about three months during the nighttime. I worked in the office during the day learning how to write speeches. I’d be sitting down somewhere in the Capitol in the middle of the night practicing writing speeches. It was a patron job, but you had a uniform, you had a gun, you had a week of training. I liked it.

N MAGAZINE: Can you share a memory from the Carter days?

N MAGAZINE: Can you share a memory from the Carter days?

MATTHEWS: You don’t know how great the old Air Force One was. You’d get on the plane at five in the afternoon and smell the steaks. [I was thinking,] “this is great. We’re going to have wine and steaks and peanuts and buckets of M&Ms.” If you asked for something, you had it. And you’d be smoking cigarettes. And you go, “This is great.” This is old 1960s living. That’s how it was working on Air Force One. It was fantastic.

N MAGAZINE: How did you end up working for Tip O’Neill?

MATTHEWS: By ’79, I became a speechwriter for President Carter. Marty Franks was a researcher for us at the White House. He called up and said, “I’ve just been made the executive director of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. We’ve lost the Senate. We’ve lost the White House. We got to make our stand in the House. Tip O’Neill needs some help.” I said, “What the heck. Don’t mess up my resume. I still want to be a presidential speechwriter so I’ll work as a consultant.” Eventually I worked behind the scenes with the Speaker. I’d give advice on little things and start writing short one-liners for him. [When] his top guy, Gary Hymel, quit a couple weeks later, he gave me the job [of Chief of Staff]. Nobody could believe it because there were so many people waiting in line. He gave me the job, and he gave me the top title and the top money. So I did that for six years, and then Tip retired.

N MAGAZINE: You wrote a bestselling book about Tip’s and Reagan’s relationship. What was at the center of that relationship?

MATTHEWS: It was a down-and-out fight, except they understood the urgency of getting things done. They had a different philosophy. They’d argued in the back room. This was authentic, true political debate. Not for the cameras. They really argued because they disagreed. Tip O’Neill was an authentic, true liberal. What I mean by that is he wasn’t some haughty, intellectual that walked around with his nose up in the air. He was a guy that cared about the average person. He was a congressman for fifty years. He would worry about the kid that couldn’t get into college.

N MAGAZINE: What has changed today where there isn’t a working relationship between Democrats and Republicans? Where did the schism start?

MATTHEWS: First of all, free air travel. [Politicians] can basically go home anytime they want [and do not hang around Washington]. Newt Gingrich came along and told the new Republican members to keep their spouses and families at home. So they all go home on the weekends. [In the past] they would have barbecues and hang out with each other and their families got to know each other. They all became great friends. [My wife] Kathy’s theory was that because they all knew each other as families, they didn’t fight to the death. Because the wife or spouse would say, “You know that guy well, cool it. Why do you make it into this big personal thing?” Now that they don’t really know each other, they fight to the death. The other thing was that the Republicans got tired of being a minority. Fifty years of being the minority does make you a little bitter. They said, “Enough of getting along with the boss, getting along with the majority. It’s time for us to play a little rough here.”

N MAGAZINE: How did you end up as a member of the media?

N MAGAZINE: How did you end up as a member of the media?

MATTHEWS: Larry Kramer called me, who had been a city editor of the Washington Post, and said, “We just lost our bureau chief to The New York Times; do you want to be Washington bureau chief of the San Francisco Examiner and run a column?” I did that in ’87 and almost immediately I was on CBS Morning News every week. That’s really what started everything. I met Roger Ailes and we clicked. We talked about doing a fast-paced TV show. When he took over CNBC and started America’s Talking, I called him up and said, “How about the show?” He said, “Okay.” We started the show in ’94 and I’ve been on every night since. It was really fortuitous that after everything else I’d done, we clicked. Whatever Roger did wrong — and I don’t doubt the facts and honest testimony — he was incredibly good as a boss. And I think a lot of people would tell you that.

N MAGAZINE: When did you start writing books?

MATTHEWS: I started writing books in ’88. I wrote Hardball, which is required reading in a lot of schools and colleges. It’s just basically to understand the culture of politics, what it was like, the way people talked, the lingo, and what is everything: retail, wholesale, background, rules, the culture, people like Tip O’Neill, Lyndon Johnson and Reagan.

N MAGAZINE: Your latest book explores the life of Bobby Kennedy. How integral was Bobby to JFK’s presidency?

MATTHEWS: Everything. He got him elected to the Senate. He ran the campaign. He was the ramrod. He was the guy that had to bring the governors in line. He had to strong-arm these guys. They would go into the room and come out scared to death with what he’d said to them. He got them in line. He kept the team in line. He was tough and ruthless for his brother. He also kept the old man in line. Joseph Kennedy had great skills as a business guy, but he had no political skills. None. And Bobby had to keep him out of the race.

N MAGAZINE: What role did Bobby play in the White House?

MATTHEWS: Starting with the Bay of Pigs, Jack relied on Bobby all the time. Bobby made the decisions in the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Civil Rights Bill of ’63, it was Bobby that pushed Jack to go on television and give that amazing speech for civil rights. On all the big issues, it’s amazing the role he played. He also integrated the University of Mississippi and the University of Alabama. He’s the guy that did the whole thing against Wallace. He’s the one that handled the Freedom Riders. I’m not saying he did it all, but he was absolutely indispensable.

N MAGAZINE: Where does Bobby Kennedy stand amongst the great leaders of history?

N MAGAZINE: Where does Bobby Kennedy stand amongst the great leaders of history?

MATTHEWS: I agree with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Bobby was one of the “two great men” who led us through the most frightening moment of the nuclear age. His central role in putting the US government on record for civil rights puts him at the inflection point in American history. For those reasons, I put Bobby Kennedy alongside his brother among our country’s indispensable leaders.

N MAGAZINE: Why is Bobby’s story particularly timely for readers today?

MATTHEWS: As I wrote in the book, Bobby Kennedy’s legacy is a statement of what we lack in 2017: a national leader committed to those in our country too often discarded and overlooked: African-Americans, Latinos and Native Americans but also those white working people cast aside by economic change.

N MAGAZINE: Have you ever thought how the trajectory of history would change had Bobby Kennedy become president?

MATTHEWS: I think he would’ve kept the compassion in the Democratic Party, caring about people whose votes really didn’t matter like Native Americans and California farm workers. He cared about them long before they became a political force. But most important to me, he would’ve kept the country together. The working-class whites and blacks, minorities—he wouldn’t have separated them. I think that was really important to him. I don’t like the fact that the Democratic Party doesn’t have the working class at its heart across the board. He wouldn’t have made that mistake. He was sticking to his roots.

N MAGAZINE: What role did the Democrats have in the rise of Trumpism?

MATTHEWS: A friend of mine in the Peace Corps said, “People don’t mind being used; they mind being discarded.” The white working class feels discarded. [The Democrats] have this combination of the elite, big entertainers from Hollywood, and the minorities—what happened to the middle class? And so Trump says, “Okay, I need you. You’re my people.” People want to be needed. Democrats didn’t say they needed them. It started with Archie Bunker in the seventies. Let’s make fun of the working-class, Irish guy. Call him a bigot and dump all over him. I think that’s the Democrats’ problem now. They just discarded people. Hillary, the “deplorables.” Everybody heard that.

N MAGAZINE: How has Trump changed politics?

N MAGAZINE: How has Trump changed politics?

MATTHEWS: There’s a difference between Trump and Trumpism. Trump you can argue about. You can talk about the clownish tweeting, the bullying and making fun of people. Some of it is truly funny: “Little Marco” and “Low-energy Jeb.” “Lying Ted.” “Crooked Hillary.” It’s high school stuff, but it worked. It’s not resume against resume. You can have the best resume in the world, but when you walk into the ring with that other guy, you’ve got to beat him in that moment. Trump always wins in that moment. It’s not about who wins the debate. It’s afterwards, who do you want to vote for?

N MAGAZINE: What do you imagine the experience is like losing the presidency?

MATTHEWS: When you lose an election and your career is over, I think every time you spill a drink or any little incident of failure echoes that you lost. Every time somebody consoles you, it hurts. I don’t think you’re going to walk away from defeat—it’s deep in you. That’s why politics is so unusual. I know Johnson never got over it. Nixon never got over it. Humphrey always looked like he had been beaten. Hillary spent a year or two thinking she was president. But Hillary’s problem was the lack of a compelling message. “Why do you want to be president?” is still the best question in the world. When you can’t answer it, it tells you everything.

EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT of BOBBY KENNEDY: RAGING SPIRIT

Written by Chris Matthews

On March 16, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy stood in the high-ceilinged, marble-walled Senate Caucus Room where, eight years earlier, his brother Jack had announced for president. Bobby now was doing the same. After months of agonizing and second-guessing, he’d decided to step up and make the commitment he’d been hanging back from, fearful the timing at this moment was wrong for his future political career.

Walking into the Caucus Room that Saturday morning was something more than a simple announcement. It was, in fact, a declaration of all-out political war. Which would see him doing battle not just on one front, but two.

The first enemy Bobby was facing down was Lyndon Johnson, the vice-president who’d taken the oath of office in the shadow of Jack’s assassination. His aggressive prosecution of the U. S. war in Vietnam had generated an ongoing national conflict, especially on college campuses.

But besides LBJ, Bobby had a second adversary, Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy, who was now holding aloft the banner of the growing anti-Vietnam War movement. The Minnesota lawmaker, with his cool professorial manner, had just, four days earlier, simultaneously thrilled the young while frightening Lyndon Johnson with a strong showing against the sitting president in the pivotal New Hampshire primary.

Thus, two very different men now obstructed the path to a Kennedy restoration.

Nonetheless, standing there at the lectern, surrounded by family members along with loyalist veterans of his brother’s campaigns, the forty-two-year-old Robert Kennedy was about to take both on. He began his statement by paying homage to his brother, a tribute clear to many listening. The opening words he’d chosen were the ones Jack had spoken in that very place: “I am announcing today my candidacy for the presidency of the United States.”

With the sentence that followed, Jack’s steadfast brother left the past behind and went straight to the heart of the troubled moment that was early 1968: “I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done – and I feel that I’m obliged to do all that I can.”

But it’s what he said next that held such power and still would today: “I run to seek new policies – policies to end the bloodshed in Vietnam and in our cities, policies to close the gaps that now exist between black and white, between rich and poor, between young and old, in this country and around the rest of the world. I run for the presidency because I want the Democratic Party and the United States of America to stand for hope instead of despair, for reconciliation of men instead of the growing risk of world war.”

Watching intently from his hotel suite in Portland, Oregon—where he himself was campaigning—was Richard Nixon, the Republican Jack Kennedy had narrowly beaten in 1960. Now certain of gaining the Republican nomination and having expected to face Johnson, the two-term vice-president turned off the TV set only to continue staring at the blank screen. He felt a foreboding. “We’ve just seen some terrible forces unleashed,” he pronounced grimly. He knew the force of the Kennedy magic knowing its power to thrill but also its power to disturb. “Something bad is going to come of this,” he added. “God knows where this is going to lead.”