At a time when few twelve-year-olds ventured far beyond their own neighborhoods, Harris Wofford boarded a transatlantic ocean liner and sailed east from New York City. The year was 1937 and the tides of change were rising fast, causing a wave of social, economic and military unrest to crest around the globe. Accompanied by his grandmother, Wofford’s first stop was in London, where he saw the king and queen and heard the early warnings of a statesman named Winston Churchill. From the United Kingdom, it was on to Paris and then Rome where he stood amidst a mass gathering and listened to the words of a fiery fascist dictator named Benito Mussolini. On Christmas Eve, he huddled in a church in Bethlehem as gunfire went off outside in the dark, during the Arab revolt of 1937-38. In Bombay, he crossed paths with Mahatma Gandhi. And in Shanghai, he sifted through the rubble from the Japanese bombardment in their conquest of most of China. After six months of extraordinary adventures, Wofford returned home to seventh grade acting, as he describes, like a “know-it-all foreign policy expert,” and declaring himself a “citizen of the world.”

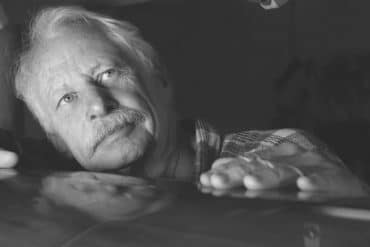

Today, Harris Wofford is no longer a young man and there is a distance to his gaze that suggests he’s seen more than most. Yet as the former Pennsylvania Senator muses upon his life from his beach home on Madequecham, an unmistakable zeal and clarity defies his eighty-six years. “By the time I had gone around the world, I had already fallen in love with the idea of America—the Founding Fathers, the Declaration, the words of Jefferson and Lincoln,” Wofford says over dinner. “When I returned with my grandmother, the world became the question to me. It fascinated me.”

The bullet points of Wofford’s life are impressive. So much so that accomplishments such as founding the Student Federalists organization in high school, or volunteering for the Army Air Corps during World War II, or being the first white student to graduate from Howard University Law, often get lost in the fine print of his many bios. Such distinctions are overshadowed by his involvement in the Civil Rights movement. When retelling of these formative times in his life, Wofford provides the listener with not only his story but also that of the day and age.

“It took most of a year in India, right after college, to make me look back on America and see more vividly that racial discrimination, segregation, the denial of the right to vote, was the shame of America, was the great blot on the American soul and the American idea in the world,” Wof- ford says. Prior to attending law school at Howard and then Yale, Wofford sailed back to India for a study fellowship in 1949 with his wife Clare, a year after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and two years since the country achieved independence. On returning, they coauthored India Afire, a book championing Gandhian nonviolence and prescribing it to the growing Civil Rights movement in the United States.

At first, many black leaders rejected the recommendations for civil disobedience and nonviolent protest. Howard University dean, William Stuart Nelson, who once visited Gandhi and urged him to come to America, wrote Wofford saying, “Reluctantly, I’ve concluded that the American Negro has no Gandhi in him.” Then came the arrest of Rosa Parks, and a young Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., rose up to lead a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. The American Negro had found his Gandhi, and Wofford became one of his close advisors.

When pressed to talk about Martin Luther King at present, Wofford takes a long pause and shuffles his hands about the table as if sifting through his memories. “My wife had never met King,” he begins, “and we picked him and his wife Coretta up in Baltimore to drive them back to Washington. In the front seat, Martin and I were talking about Gandhi strategy and we heard Coretta say to my wife, ‘You know Clare, ever since Martin chose this course, I’ve had a nightmare that at the end of it, he’s going to be killed.’ King turned around and said, ‘Corey, I keep telling you to take that nightmare out of your head, and think of all the things that we can do now. I didn’t choose this course. You know I didn’t choose this course. They asked me to take the lead in the bus boycott and I said yes.’” Wofford looks up and concludes the account: “And then he hummed a spiritual. I’m not going to sing it, but the thrust was: ‘The Lord came by and asked, and my soul said yes.’”

While much can be said about Wofford’s political mark on the 1960s, his involvement is encapsulated in what’s become known as The Call. After becoming a close colleague of King’s, Wofford went on to work on John F. Kennedy’s 1960 Presidential bid, as deputy to Sargent Shriver in the campaign’s Civil Rights Section. Kennedy was struggling to secure the black vote, some of which opposed him because of his Catholic faith. Then on October 19, 1960, King was arrested at a sit-in in an Atlanta restaurant, along with fifty-one others. Although initially released with the other protesters, King was rearrested and taken to a county prison outside of Atlanta and then in shackles to a faraway state prison. The judge sentenced him to four months hard labor. It became a front-page story in the American press and around the world it was treated as a scandal.

Fearing that her husband was going to be killed, Coretta King, who was five months pregnant, called Wofford in a panic, hoping he could do something. Knowing that Kennedy did not want to intervene publicly with the court process, Wofford suggested to Shriver that he urge Kennedy to intercede on an emotional level and phone Coretta King to extend his personal sympathy and concern. Shriver took the idea directly to Kennedy, who thought briefly and then asked for her phone number and made the call.

The story of Kennedy’s empathy and the warm words of thanks from King himself, spread quickly through the black community in the last ten days of the campaign (with help from Shriver and Wofford). By all accounts the im- pact of Kennedy’s call swayed many black votes, north and south. With a margin of only 112,827 popular votes, Kennedy’s victory in the Electoral College depended on states where the large increase in black votes from the 1956 election made the difference. Among the many factors necessary for his victory, Kennedy’s call ranks as one of them—a footnote to how the course of history can be changed.

“When people say to me, ‘How lucky you were to have worked directly with John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King,’ I say, some luck! The three people that meant the most to me during that part of my life were all killed.” Wofford then corrects himself, “But I was lucky. We were all lucky to have had them in our national life. I predominately think of myself as a comic character, in the broad meaning of comedy. But I have been close to real tragedies such as the Vietnam War and the assassination of our best leaders in the middle of the 20th century.”

Through all the comedy and tragedy of his years, Wofford went on from serving as Special Assistant to the President for Civil Rights in Kennedy’s first five hundred days to become the Peace Corps’ representative to Africa and eventually to be Sargent Shriver’s Associate Director of the Peace Corps in Washington. In 1966, he entered academia as the founding president of State University of New York’s new College at Old Westbury. In 1970, he became president of Bryn Mawr College.

After the tragic death of U.S. Senator John Heinz in 1991, Wofford was appointed senator, with six months to win the seat in a special election against former governor and then U.S. Attorney General, Dick Thornburgh. Wofford’s surprise landside victory was attributed widely to his campaign theme of universal health care. The late Ted Kennedy credited him with carrying that banner of health care into the Senate, but by the Republican wave of 1994, the banner was in tatters, after the failure of the Clinton plan. Wofford calls it “a fiasco” for both the Congress and the President—and for himself as he lost his reelection by a nar- row margin to Rick Santorum.

But Wofford says he has no complaint: “At sixty-five, I had the chance to be Pennsylvania’s Senator, and we did pass the National Service Act of 1994, a goal I’ve had since 1965 when I helped Sargent Shriver create VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) as a key part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty. And in all the years since, I’ve been in the front lines of the campaign for large scale National Service.” He points to President Bill Clinton’s call on him to help save AmeriCorps, as CEO of the embattled Corporation for National and Community Service. The House of Representatives had voted to terminate it, but Clinton and the Senate held firm and AmeriCorps grew to fifty thousand on Wofford’s watch. After 9/11, President Bush called on Congress to enable AmeriCorps to grow to 75,000, and Wofford was a leader in building the nation-wide coalition that helped make that happen.

After dinner, Wofford leads me down to the edge of his property overlooking the shores of the Atlantic. He and his wife Clare purchased the land in 1977, and ever since the ocean has stripped away an average of four feet of beach per year. Some years, the ocean gives back a little. And so it has been with Wofford’s public life: losing some— King and the Kennedys —and gaining some— Barack Obama. In 2008, Wofford introduced the future president in Philadelphia just before he delivered his now famous speech, “A More Perfect Union.” Watching Obama in Philadelphia, Wofford says he saw shades of King and Kennedy in this next generation of American leader, the culmination of a march he felt privileged to have been a part. Looking now at a country divided and mired in partisanship, Wofford quotes what the philosopher Martin Buber said to him in Jerusalem shortly after Kennedy was killed: “‘Good ideas will rise again and come back when idea and fate once more meet in a creative hour.’” He turns to the horizon. “I realize that I am yearning to be around the next time when idea and fate cross again in a creative hour.”