How the next generation of Nantucketers is keeping our shellfishing tradition alive.

Shellfishing stretches back hundreds of years on Nantucket. Before the first European settlers arrived to the island, the Wampanoags were already harvesting scallops, oysters, and hard and soft-shelled clams that they dried and smoked for the long winter months. The surrounding eel grass beds in Nantucket’s waters served as ideal habitats for clams, quahogs, and, most especially, Nantucket Bay Scallops.

But since the commercial harvest for these shellfish began in the mid-1870s, there’s been a gradual decline in numbers, which has continued to diminish in recent years due to varied water quality, struggling eel grass beds, and a host of other environmental factors. Thankfully, there’s a select group of Nantucketers who are helping keep this industry and tradition alive in their own unique ways.

HANG TEN RAW BAR

Emil Bender & Sean Fitzgibbon

When Emil Bender graduated from Brandeis University with a degree in environmental science three years ago, he couldn’t picture himself at a desk job. He’d spent summers working at his father’s oyster farm off Pocomo Point and knew the challenges and rewards of a life on the water. So he moved back to Nantucket, partnered up with his father on the farm’s day-to-day operations, and then started Hang Ten Raw Bar with childhood buddy Sean Fitzgibbon.

When Emil Bender graduated from Brandeis University with a degree in environmental science three years ago, he couldn’t picture himself at a desk job. He’d spent summers working at his father’s oyster farm off Pocomo Point and knew the challenges and rewards of a life on the water. So he moved back to Nantucket, partnered up with his father on the farm’s day-to-day operations, and then started Hang Ten Raw Bar with childhood buddy Sean Fitzgibbon.

Emil’s father Steve Bender founded Pocomo Meadow Oyster Farm in 2009 near the mouth of Polpis Harbor, where tidal creeks and ground-fed freshwater springs lend the oysters a briny sweetness. The farm is a sustainable, farm-to-table resource. Most mornings begin at low-tide when oysters are harvested for the local restaurants as well as for Hang Ten Raw Bar, which Emil and his partner Sean Fitzgibbon bring to weddings, private dinners, beach parties and corporate events. “We’re personally getting out and harvesting all the shellfish that we’re serving to people,” Fitzgibbon says. “So we have a connection to the island and to the food system that’s very special.”

Sean Fitzgibbon graduated in 2012 from Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Boston and works as a private chef. He’s also one of the fastest oyster shuckers on Nantucket, having earned the distinction at a local contest last year. Fitzgibbon loves using fresh ingredients, and forages for his own wild clams in addition to the oysters he and Emil gather each morning. “Sourcing foods closer to home is a big part of people’s mindset,” Fitzgibbon says. “Everyone wants to go local. We can promise that our oysters pass through only two sets of hands before they get eaten.”

Sean Fitzgibbon graduated in 2012 from Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Boston and works as a private chef. He’s also one of the fastest oyster shuckers on Nantucket, having earned the distinction at a local contest last year. Fitzgibbon loves using fresh ingredients, and forages for his own wild clams in addition to the oysters he and Emil gather each morning. “Sourcing foods closer to home is a big part of people’s mindset,” Fitzgibbon says. “Everyone wants to go local. We can promise that our oysters pass through only two sets of hands before they get eaten.”

TOWN OF NANTUCKET

Leah Cabral

While summer visitors and locals perch on barstools slurping down succulent oysters, Leah Cabral slips into alleys behind restaurants to collect blue plastic tubs filled with discarded shells. She hoists them into a town-owned Ford pickup and drives to Madaket, where she dumps them on a growing mountain of shells awaiting their turn to become nurseries for baby oysters.

While summer visitors and locals perch on barstools slurping down succulent oysters, Leah Cabral slips into alleys behind restaurants to collect blue plastic tubs filled with discarded shells. She hoists them into a town-owned Ford pickup and drives to Madaket, where she dumps them on a growing mountain of shells awaiting their turn to become nurseries for baby oysters.

Cabral always knew she wanted to be a marine biologist. Before joining Nantucket’s Natural Resources Department as an assistant biologist in 2014, she’d helped communities as far away as Eleuthera and Zanzibar farm native species of fish and clams. She’s now spearheading an effort to replenish Nantucket’s shellfish beds in the face of a worldwide decline. “People are realizing oyster shells are a limited resource,” she says. “We need to get the oyster population on the increase by restoring reefs that have succumbed to pollutants and disease. Part of that effort is reclaiming shells from consumers, restaurants and oyster farmers.”

Oysters once thrived in the Monomoy creeks off Shimmo and Coatue, near the town wharves. Now, thanks to eight aquaculture growers and the town shellfish hatchery, housed in a small white structure on stilts next to Brant Point light, there are populations at the head of the harbor, in Coskata Pond and near Polpis Harbor. What’s more, free-floating larvae—tiny brownish baby oyster blobs fattening up on algae until they attach to the shell that will become their home—are forming new natural beds in Easy Street basin and at the Jetties. And as of June, oysters cultivated at the Nantucket hatchery are growing on a one-acre reef in Shimmo Creek fashioned from 100,000 pounds of reclaimed shells. There are plenty more where those came from. In peak season, Cabral and others pick up shells from more than two dozen local restaurants seven days a week: 12,000 pounds a month in July and August alone, for a total of around 20 metric tons.

Cabral got a first-hand feel for shell fishing in winter 2013, when she worked alongside conch-fisherman-turned-oyster-farmer Andy Roberts of Retsyo Oysters. Roberts launched Retsyo (oyster spelled backwards) in July 2011 after more than 25 years of fishing for conch in the summer and harvesting Nantucket bay scallops in the winter. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Cabral says of commercial scalloping. “It was tough. You go out at 6 am. The wind’s blowing, it’s cold. You definitely need some upper-body strength, which I had by the end of the season.”

Cabral got a first-hand feel for shell fishing in winter 2013, when she worked alongside conch-fisherman-turned-oyster-farmer Andy Roberts of Retsyo Oysters. Roberts launched Retsyo (oyster spelled backwards) in July 2011 after more than 25 years of fishing for conch in the summer and harvesting Nantucket bay scallops in the winter. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Cabral says of commercial scalloping. “It was tough. You go out at 6 am. The wind’s blowing, it’s cold. You definitely need some upper-body strength, which I had by the end of the season.”

Cabral says she doesn’t often eat oysters because of their brininess. Bay scallops are her favorite. Pulling up oysters and scallops from the chilly waters, Cabral felt a connection to the ocean. “I’m learning the process because it is important here on Nantucket, and it has been for hundreds of years,” she says. “So it was just really cool to learn how to do what our ancestors did years ago.”

NANTUCKET BAY SCALLOP TRADING CO.

The Whelden Brothers

The Whelden brothers’ connection to Nantucket’s shell fishing industry stretches back four generations to their great-grandfather Elliot Whelden who commercially fished on the island. During the seventies, their grandfather Ernie and father Larry expanded the family fishing business to distributing Nantucket bay scallops to the mainland and opening a restaurant on the island — an eatery that was to become the beloved Lobster Trap.

The Whelden brothers’ connection to Nantucket’s shell fishing industry stretches back four generations to their great-grandfather Elliot Whelden who commercially fished on the island. During the seventies, their grandfather Ernie and father Larry expanded the family fishing business to distributing Nantucket bay scallops to the mainland and opening a restaurant on the island — an eatery that was to become the beloved Lobster Trap.

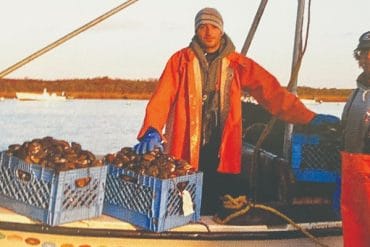

A decade ago, this fourth generation of Whelden men — John, Drew and Alex — took over The Lobster Trap and have continued the tradition of exporting scallops to the mainland through their Nantucket Bay Scallop Trading Company, which they launched six years ago. “Initially we would freeze our catch for the restaurant, but soon came the idea of offering fresh scallops to anyone and everyone,” say the Whelden brothers. “We wanted to give people the experience of having the freshest Nantucket bay scallops right from the source.” Beyond Boston, their scallops have been shipped as far as Arizona, Colorado, California and even Hawaii.

Just as their father, grandfather and great grandfather before them, the Wheldens relish the opportunity to make a living on the water. After the hustle and bustle of running The Lobster Trap during the summer, the beginning of the commercial scalloping season in November is a welcomed reprieve. Every time they head out, the three brothers continue writing their own chapter in the family’s long history harvesting Nantucket’s waters. “It is a very unique thing we have here in our Nantucket harbors and it is a huge part of the island’s history and tradition,” Drew Whelden says. “We feel lucky to be a part of the history and tradition.”

Just as their father, grandfather and great grandfather before them, the Wheldens relish the opportunity to make a living on the water. After the hustle and bustle of running The Lobster Trap during the summer, the beginning of the commercial scalloping season in November is a welcomed reprieve. Every time they head out, the three brothers continue writing their own chapter in the family’s long history harvesting Nantucket’s waters. “It is a very unique thing we have here in our Nantucket harbors and it is a huge part of the island’s history and tradition,” Drew Whelden says. “We feel lucky to be a part of the history and tradition.”

LEGASEA RAW BAR CO.

PJ Kaiser

Peter Kaizer, Jr. remembers tagging along as a kid while his dad gave shellfish, striped bass and cod to friends and family all over town, sharing the bounty of the day’s catch. The elder Pete Kaizer, a commercial tuna fisherman turned charter boat captain, has worked the waters around Nantucket for more than four decades. “Bluefin tuna fisherman, cod fisherman, you name it, he pretty much fished for it in the ‘70s and ‘80s,” says Peter Jr., who goes by PJ.

Peter Kaizer, Jr. remembers tagging along as a kid while his dad gave shellfish, striped bass and cod to friends and family all over town, sharing the bounty of the day’s catch. The elder Pete Kaizer, a commercial tuna fisherman turned charter boat captain, has worked the waters around Nantucket for more than four decades. “Bluefin tuna fisherman, cod fisherman, you name it, he pretty much fished for it in the ‘70s and ‘80s,” says Peter Jr., who goes by PJ.

But for PJ, who also works as a commercial lending officer for Cape Cod Five and serves as a member of the board of directors of the Egan Maritime Institute, the family fishing tradition he continues is not his father’s, but that of his uncle Stephen Kania — better known around the island as Spanky of the legendary Spanky’s Raw Bar.

Spanky “shepherded me into starting my own business,” says PJ. “It’s been very word of mouth.” PJ learned the ropes by occasionally staffing raw bars in Boston for his uncle, then working for him more regularly after he moved back to Nantucket in 2010. With his uncle’s blessing, PJ then launched his own raw bar called Legasea. “It’s nice to have something that keeps me tied to the long-time fishing and shellfish background that my family established on the island,” he says. “Nantucket’s got such a rich marine maritime heritage. When you live here, it feels right to try to build something that will live on.”

Spanky “shepherded me into starting my own business,” says PJ. “It’s been very word of mouth.” PJ learned the ropes by occasionally staffing raw bars in Boston for his uncle, then working for him more regularly after he moved back to Nantucket in 2010. With his uncle’s blessing, PJ then launched his own raw bar called Legasea. “It’s nice to have something that keeps me tied to the long-time fishing and shellfish background that my family established on the island,” he says. “Nantucket’s got such a rich marine maritime heritage. When you live here, it feels right to try to build something that will live on.”