Celebrating the words of the late great David Halberstam.

This spring marked the tenth anniversary of David Halberstam’s tragic death. A beloved Nantucket summer resident and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Halberstam was praised by the likes of the Washington Post as “the greatest reporter of our time.” In 2003, N Magazine had the privilege of profiling Halberstam for the cover story of our July issue. “The island has always been a great sanctuary for me,” he said during our interview. “I’ve always felt protected here… Every day I’m aware of the great sense of renewal that Nantucket has given me. Without it, I don’t think I would have had as rich a life, professionally or personally.” In 1999, Halberstam mused upon his life on the island in a piece for Town & Country titled “Nantucket on My Mind.” Now as much as then, Halberstam’s words not only capture the power of this place, but also the unique people it attracts.

This spring marked the tenth anniversary of David Halberstam’s tragic death. A beloved Nantucket summer resident and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Halberstam was praised by the likes of the Washington Post as “the greatest reporter of our time.” In 2003, N Magazine had the privilege of profiling Halberstam for the cover story of our July issue. “The island has always been a great sanctuary for me,” he said during our interview. “I’ve always felt protected here… Every day I’m aware of the great sense of renewal that Nantucket has given me. Without it, I don’t think I would have had as rich a life, professionally or personally.” In 1999, Halberstam mused upon his life on the island in a piece for Town & Country titled “Nantucket on My Mind.” Now as much as then, Halberstam’s words not only capture the power of this place, but also the unique people it attracts.

Nantucket on My Mind

Written by David Halberstam

This is my thirtieth year as an owner here. I bought my house in 1969, the year I began working on “The Best and the Brightest,” the moment when I went over to writing books full time. Over the years I have come to love the island – it has given me sanctuary in a difficult and often volatile professional life, allowing me to work diligently each summer while putting myself back together among people who I know love and care about me. I leave the island in the early fall rested, but with a great deal of work done. I stumbled on it at first – my friend Russell Baker brought me here in 1968 and I thought it was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. It seemed to have more of the good things of life and fewer of the bad than any vacation spot I had ever seen before; it offered an almost-perfect balance between the possibilities for friendship and the right, when I needed to work, to my privacy. Because the happiest part of my peripatetic childhood was spent in a small town in northwest Connecticut, Nantucket – with its strikingly handsome library, the sense of community manifest at high school games – reminded me of the best part of my youth. People knew one another and treated one another with respect. The people who did have money (and it would be considered small money these days), those old Yankee families said to be very wealthy, very consciously did not manifest it. In the great houses along Hulbert Avenue, our showcase street that runs along the harbor, the houses were, as they always had been, a little worn down, with bathroom sinks stained green by the relentless drip of the water – a reminder of plumbers never summoned.

It was still very much a middle-class island in those days. Unlike other East Coast watering holes, we did not have much in the way of a writer’s community, and that too appealed to me, because I had spent one summer in the Hamptons and the pace of the social life had been far too intense.

My own social circle was eclectic, filled largely with people I would not have been friends with in New York – people I fished with, or, in time, those my wife and I enjoyed cooking with. Not surprisingly, as our daughter grew up, our friends were people who had children who were her friends.

We formed, I think, the squarest of summer communities. Our friends were, it seemed to me, people brought to Nantucket not because it was chic but because it was beautiful and family-oriented, and because they liked the pleasures of the island – the fishing, the sailing, the tennis, and the birding, things that, as they did for me, recalled the happier parts of their own childhoods, even if they now lived in tough, demanding urban environments.

We formed, I think, the squarest of summer communities. Our friends were, it seemed to me, people brought to Nantucket not because it was chic but because it was beautiful and family-oriented, and because they liked the pleasures of the island – the fishing, the sailing, the tennis, and the birding, things that, as they did for me, recalled the happier parts of their own childhoods, even if they now lived in tough, demanding urban environments.

Soon it was the texture of friendships as much as the beauty of the island that held us, friendships that were not work-connected and that near the end of the spring we always looked forward to renewing. Those friendships were based on simple things: fishing with my friend David Fine; going to the beaches with Pam and Foley Vaughan and their children; dinner with Bill Euler and Andy Oates, who ran our best store, Nantucket Looms, a friendship tentative at first because they were so private; rowing in a double scull with Marc Garnick; and finally, after I sold my fishing boat, fishing with Tom Mleczko, who doubled as a schoolteacher in New Canaan the rest of the year. These were the touchstones of our summer, the friendships sweetened by the many years in grade from the past.

There was over the years, starting in the eighties, a dramatic change in the cast of characters who came here – the rising prices on the tickets of the houses automatically narrowed down the possibilities of who could afford the island. (One summer I called a friend of mine who was a journalist and asked if he was going to rent again. No, he answered, the rent had just tripled, and so he was going to Tuscany for a month – it was cheaper.) In addition, I thought I sensed a change in what people sought from this island – an increase in the importance of status. That has been particularly noticeable in the last few years with the coming of such stupendous wealth, wealth that seems with its vast annual rewards disconnected from the reality of daily life. I realize there is some degree of generalization to what I am going to say, and I am sure that some of the new people are as nice or nicer than the old, and that some of the older people, given half a chance, would be greedier than the new. But I am not sure that the new people are brought to the island by the old and abiding pleasures that drew us.

The new people seem not only very rich, but very young to be that rich; and all too often they seem quite imperious. I suppose that is not too surprising; they have been raised in a modern pressure cooker: starting out in demanding day schools, and then demanding boarding schools, and then making the cut at demanding elite colleges, and then again making the next level, at demanding law or business schools, and then becoming winners in the brutal competition in the world of finance. There, if you are a winner, an annual award of $10 million is thought to be small; it is where people now talk of making a unit – a unit being earnings of $25 million in a year. I think something like that begins to affect a person’s sense of proportion.

On our island we are, I think, the worse for it. There is a sharp, indeed an alarming, decline in the requisite courtesy and manners that are so critical to the texture of life in a small town, and that are, comparably, so unimportant in a city like New York. When these people want things – houses to be built, gardens to be made green, rugs to be woven and delivered – they want them right now, with a special immediacy, as if they were back in the city ordering out from a neighborhood Chinese restaurant. If they buy a piece of property for $2.5 million and plan to tear it down and build a new house for $3 million, the money is no longer an object – but the speed of completion is. By July 1, if you please – otherwise we’ll have to go elsewhere. That has a ripple effect throughout the island – the cost of everything goes up accordingly, and other work orders, small assignments, the repair of a house here, an addition to a house there, tend to be shunted aside. Two summers ago, our gardener fired us because all we wanted was upkeep on our garden, and it was impossible for us to compete with the gargantuan projects offered her by newer arrivals.

On our island we are, I think, the worse for it. There is a sharp, indeed an alarming, decline in the requisite courtesy and manners that are so critical to the texture of life in a small town, and that are, comparably, so unimportant in a city like New York. When these people want things – houses to be built, gardens to be made green, rugs to be woven and delivered – they want them right now, with a special immediacy, as if they were back in the city ordering out from a neighborhood Chinese restaurant. If they buy a piece of property for $2.5 million and plan to tear it down and build a new house for $3 million, the money is no longer an object – but the speed of completion is. By July 1, if you please – otherwise we’ll have to go elsewhere. That has a ripple effect throughout the island – the cost of everything goes up accordingly, and other work orders, small assignments, the repair of a house here, an addition to a house there, tend to be shunted aside. Two summers ago, our gardener fired us because all we wanted was upkeep on our garden, and it was impossible for us to compete with the gargantuan projects offered her by newer arrivals.

The houses being built are different now. The old Nantucket had houses of modest size, and in keeping with the traditional respect for the sheer beauty of the island, they were often nestled in the landscape itself. By contrast, many of the new houses are huge flag-ships to show that yes, there is a great deal of wealth in the family, and they seem to violate the natural contours of the land as violently as possible. The cars on our island are bigger and fancier, too – they used to be deliberately downscale, and exceptionally well rusted, but these days everyone seems to be driving sport-utility vehicles (SUVs, to use the vernacular) that seem to be like jeeps on steroids.

Worse, the manners of the drivers seem to have declined in inverse proportion to the size of their cars and wealth. Many of our rural roads are paths more than roads, and it was common courtesy, when you were driving down a rural road wide enough for only one car and you spotted a car coming at you, to pull over if at all possible in a niche alongside the road and let the other car go by. Part of that same courtesy was for the driver of the other car to wave as he or she went by signaling some respect for your manners – as if to say, you did it for me this time, I’ll do it for you the next. Now you pull over – you had better, because the other car is sure to be twice as big and powerful as yours – and more often than not, there is not the slightest wave of the hand or the beep of a horn. They are telling you that you pulled over because it is your proper place in the universe to pull over for them – and you’d better be prepared to pull over the next time as well.

Somewhere in here is no small amount of money. The island is more crowded than ever, more gentrified than ever, and there is more building going on than ever before, more huge trucks bearing down on our narrow streets and roads. Yet if the island is more crowded, I suspect it manages to remain aloof from many of its most ardent new suitors. I have this theory – that many of the true pleasures of Nantucket are not easily gained and cannot be purchased on demand, that they have to be, like everything else in life, earned, and you have to take time and serve something of an apprenticeship in order to get the full measure of the pleasures available.

Somewhere in here is no small amount of money. The island is more crowded than ever, more gentrified than ever, and there is more building going on than ever before, more huge trucks bearing down on our narrow streets and roads. Yet if the island is more crowded, I suspect it manages to remain aloof from many of its most ardent new suitors. I have this theory – that many of the true pleasures of Nantucket are not easily gained and cannot be purchased on demand, that they have to be, like everything else in life, earned, and you have to take time and serve something of an apprenticeship in order to get the full measure of the pleasures available.

For all of the crowding downtown, many of the beaches remain secluded, the nature walks are pleasant and accessible, and there is no time for them. If you want to picnic, and have a boat, there are places in Polpis, the large inner harbor, where, if you know the tides, you can miraculously enough go and picnic in a beautiful spot – more of an idyll than one can imagine on the East Coast – and never see another soul. I am a fairly serious fisherman, and our light-tackle saltwater fishing is arguably the best along the East Coast, perhaps because we are so far into the Gulf Stream. But it takes time and skill to learn how to fish here, and money will not do it all for you – you have to learn to handle a boat in what are daunting waters, going out on days when the weather changes, when the shoals are murderous and when the fog rolls in so suddenly that unless you know what you are doing, it can all be quite terrifying. I know, because I had a boat for ten years, and it was a difficult and exacting apprenticeship, not so much learning where the fish are – that part was easy – but how dangerous the Atlantic Ocean can be. So perhaps it is not surprising that, for all the money being spent on boats, many of them with GPS/Loran guides that should make dealing with fog and shoals virtually idiot-proof, on the July Fourth and Labor Day weekends, the most crowded days of the year, you can be at choice spots for fishing for blues or stripers only thirty minutes from Madaket Harbor and not see another boat.

I realize that what I’m writing reflects not just the change in the economy but the change in the writer himself, the changes in the eye of the beholder: that the adventurousness of a young man come to a new place in his thirties is very different from a man in his sixties, wanting things always to be as they once were, bemoaning, almost unconsciously, the loss of his own youth. And I am aware that one of the critical things I liked about the island remains as true as ever: that it can, in a country as dynamic and volatile as ours, offer you a sense of the seasons of your own life, as life in a city rarely can, the kind of texture and feeling that Thornton Wilder captured in “Our Town” – a sense of the rhythm of your life as it touches those around you. If over the years we have had friends who for various reasons have moved away, and if our list of friends is not exactly what it was two decades ago, there is nonetheless a sense of being rooted here as we are not rooted in New York, and an ability to monitor the seasons of our lives from the changes in the lives of those around us.

In New York our friendships tend to be with peers, more often than not professionally driven, and while we tend to know the children of our friends, by and large, with few exceptions, the friendships bloom in the evening and the children tend to remain in the background, seen but not really known. That is not true of Nantucket: over the past thirty years I have watched the children of my friends grow up, go off to college, and come back and have children of their own. I have fished with my friend David Fine for twenty-eight years now, and our routines aboard the boat – who will catch the first or the biggest fish – have the quality of old Vaudeville routines, the sweetness of conversations so oft repeated that they have by now become second nature. Paul and Joan Crowley became our friends because they were friends of David and Sue Fine’s, and in time we watched Melissa Crowley grow from a young girl and a superb athlete to a confident, extremely successful magazine editor in New York. Both David Fine and I in time gave up running our own boats, and we have fished for the last few years with Tom Mleczko, who is our best fisherman, and we have had the pleasure of seeing his and Bambi’s children, who worked as strikers on his boat, grow up to become strikingly handsome young people, one daughter in Boston, a son about to start college, and another daughter, whom I wrote about, become a star of the championship U.S. Olympic hockey team, an article that gave me as much pleasure as anything I’ve ever written. Their cousins, the Gifford kids – how many letters written to directors of admission at different boarding schools and colleges? – have morphed into tall, handsome, confident young men and women. John Burnham Schwartz, who appeared with his parents at my house when he was nine, beautiful and beguiling, and whom I used to take fishing every summer, has remained a friend and the light of my life. We gave his engagement party and the book party for his second novel; he is now a successful novelist, and a peer, someone I count on not merely for friendship but for advice.

In New York our friendships tend to be with peers, more often than not professionally driven, and while we tend to know the children of our friends, by and large, with few exceptions, the friendships bloom in the evening and the children tend to remain in the background, seen but not really known. That is not true of Nantucket: over the past thirty years I have watched the children of my friends grow up, go off to college, and come back and have children of their own. I have fished with my friend David Fine for twenty-eight years now, and our routines aboard the boat – who will catch the first or the biggest fish – have the quality of old Vaudeville routines, the sweetness of conversations so oft repeated that they have by now become second nature. Paul and Joan Crowley became our friends because they were friends of David and Sue Fine’s, and in time we watched Melissa Crowley grow from a young girl and a superb athlete to a confident, extremely successful magazine editor in New York. Both David Fine and I in time gave up running our own boats, and we have fished for the last few years with Tom Mleczko, who is our best fisherman, and we have had the pleasure of seeing his and Bambi’s children, who worked as strikers on his boat, grow up to become strikingly handsome young people, one daughter in Boston, a son about to start college, and another daughter, whom I wrote about, become a star of the championship U.S. Olympic hockey team, an article that gave me as much pleasure as anything I’ve ever written. Their cousins, the Gifford kids – how many letters written to directors of admission at different boarding schools and colleges? – have morphed into tall, handsome, confident young men and women. John Burnham Schwartz, who appeared with his parents at my house when he was nine, beautiful and beguiling, and whom I used to take fishing every summer, has remained a friend and the light of my life. We gave his engagement party and the book party for his second novel; he is now a successful novelist, and a peer, someone I count on not merely for friendship but for advice.

The friendship with Bill Euler and Andy Oates, a bit hesitant at first, grew stronger every year, and dinners with them became the evenings we looked forward to with singular pleasure, in time raucous evenings of more wine than normal and world-class gossip. Five years ago I dedicated a book to them (it was a base- ball book, and someone, not knowing of our friendship, saw their names and asked “Euler and Oates – which team did they play for?”). This year, Bill, who was my age, died of leukemia, and it was like nothing so much as a death in the family, for he was a shy man who had quietly enhanced many other people’s lives, and seemed not to know how much he was cherished and how much he would be missed. We’ve watched our own child, and those of our friends the Vaughans and the Clapps and the Durkes, grow up together and go off to college. Our daughter on occasion reminds us that she thinks of Nantucket, not New York, as her real home and thinks about living in our old house someday with her own children. And when she talks like that, we are reminded that we have become in some way of the island, that it binds us and forms our lives in ways we do not entirely understand, and yet are unconsciously dependent upon.

The places you love will do that to you.

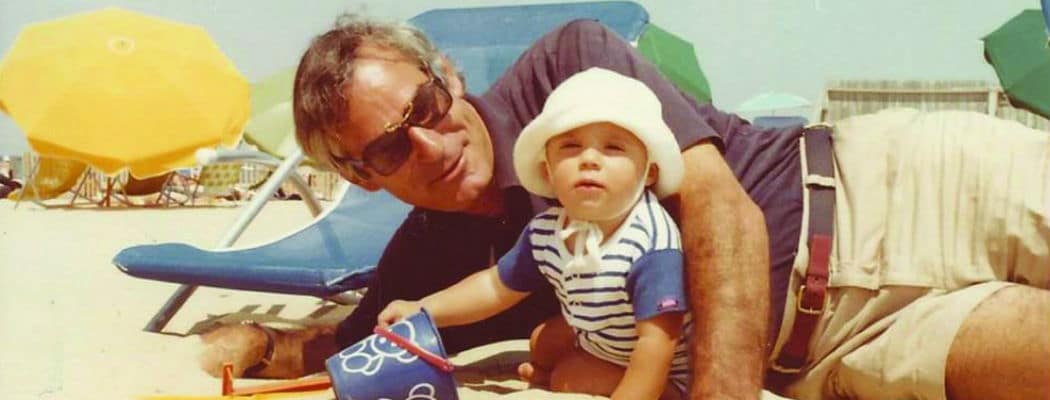

“Nantucket on My Mind” was reprinted with permission from Julia Halberstam in accordance with Town & Country. Photos of David Halberstam on Nantucket were provided courtesy of Julia Halberstam.