The incredible story of a man, his boat and his voyage to Nantucket.

Lydia Sussek was standing in line at the Steamship Authority last June when she heard an old man in distress. She couldn’t make out exactly what he was saying until she realized the man was speaking in Italian. Sussek, a part-time island resident who is fluent in Italian, jumped ahead in line to see if she could help serve as his translator. The man was nearly in tears struggling to communicate to the ticket clerk that he had just missed the ferry and needed to find another way back to the Cape. Sussek pulled him aside and said she’d help get him off the island. As they walked together to the Hy-Line to catch the next ferry, the man began telling Sussek how he found his way to Nantucket from his home in Venice, Italy. It was a harrowing tale that could have been pulled from the pages of Robinson Crusoe.

Lydia Sussek was standing in line at the Steamship Authority last June when she heard an old man in distress. She couldn’t make out exactly what he was saying until she realized the man was speaking in Italian. Sussek, a part-time island resident who is fluent in Italian, jumped ahead in line to see if she could help serve as his translator. The man was nearly in tears struggling to communicate to the ticket clerk that he had just missed the ferry and needed to find another way back to the Cape. Sussek pulled him aside and said she’d help get him off the island. As they walked together to the Hy-Line to catch the next ferry, the man began telling Sussek how he found his way to Nantucket from his home in Venice, Italy. It was a harrowing tale that could have been pulled from the pages of Robinson Crusoe.

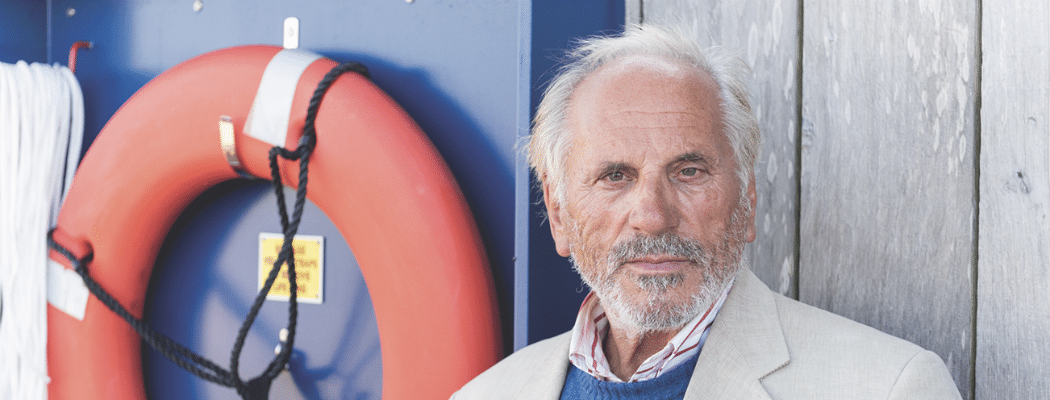

More than a year earlier, Vittorio Fabris, at the age of seventy-seven, had loaded up his thirty-three-foot sloop named Mia in Venice and set sail for Nantucket. His voyage was inspired by Moby-Dick. During his time working as a fishmonger, Fabris observed how pollution and overfishing were devastating the ocean. In sailing alone to Nantucket, he hoped to symbolically pay homage to nature and do penance for mankind’s destruction of the whales’ habitat. To commemorate the voyage, a Venetian artist created a whale-inspired sculpture that Fabris would deliver to the Nantucket Whaling Museum at the end of his journey. Before leaving the port in April 2018 he hung a big banner along his portside gunnel reading in English: I’M GOING TO APOLOGIZE TO THE WHALE.

While he was flush with inspiration, Fabris was short on experience. He had only begun sailing fifteen years earlier and had never attempted an open ocean crossing by himself. Fabris planned to navigate the 20,000 miles to Nantucket over the course of a month along some of the same historic whaling routes detailed in Moby-Dick. But after sailing successfully through the Mediterranean and the Strait of Gibraltar, Fabris hit an unknown object around the Azores that he thought might have been a whale, and was forced to return to Spain. When he attempted the crossing again, his automatic steering malfunctioned, sending the Mia back onshore to get repairs. When he set sail again two months later, hurricane season was bearing down, sending him on a circuitous route south to make stops in the Canary Islands and Cape Verde before heading across the Atlantic.

While he was flush with inspiration, Fabris was short on experience. He had only begun sailing fifteen years earlier and had never attempted an open ocean crossing by himself. Fabris planned to navigate the 20,000 miles to Nantucket over the course of a month along some of the same historic whaling routes detailed in Moby-Dick. But after sailing successfully through the Mediterranean and the Strait of Gibraltar, Fabris hit an unknown object around the Azores that he thought might have been a whale, and was forced to return to Spain. When he attempted the crossing again, his automatic steering malfunctioned, sending the Mia back onshore to get repairs. When he set sail again two months later, hurricane season was bearing down, sending him on a circuitous route south to make stops in the Canary Islands and Cape Verde before heading across the Atlantic.

Sailing offshore in any size vessel is dangerous. Sailing across the Atlantic in a thirty-three-foot sailboat, alone, at nearly eighty years old, sounds like a death wish. But Fabris relished his time alone. His only company was a stack of books and a volleyball that he fashioned to look like “Wilson” from the Tom Hanks film Castaway. By the time he reached Guadeloupe in the Caribbean and began heading north along the East Coast to Nantucket, Fabris had been at sea on and off for more than a year. He hoped that this final leg of his journey would consist of two weeks of smooth sailing—but as it turned out, the worst was yet to come.

Sailing offshore in any size vessel is dangerous. Sailing across the Atlantic in a thirty-three-foot sailboat, alone, at nearly eighty years old, sounds like a death wish. But Fabris relished his time alone. His only company was a stack of books and a volleyball that he fashioned to look like “Wilson” from the Tom Hanks film Castaway. By the time he reached Guadeloupe in the Caribbean and began heading north along the East Coast to Nantucket, Fabris had been at sea on and off for more than a year. He hoped that this final leg of his journey would consist of two weeks of smooth sailing—but as it turned out, the worst was yet to come.

Fabris encountered two massive storms off the coasts of North Carolina and Long Island. During one of these squalls, he clung to his mast while a Coast Guard helicopter hovered overhead, trying to convince him to abandon ship. But Fabris refused. After two months of brutal sailing up the East Coast, Nantucket finally came into sight the Friday of Memorial Day weekend. He’d spent fourteen months at sea, covered tens of thousands of miles and had dozens of close calls, but Fabris finally felt like he was home free. Fifteen-hundred feet from shore, he stowed his sails and turned on his engine to motor to the dock for his illustrious arrival—but then his engine died. Fabris started to drift, the current pushing him towards the shallows along the Cliffs. He rushed to throw an anchor, but before he could, the Mia ran aground and capsized.

With the wind and tide pushing and pulling him away from the entrance to the harbor, the sailor sent out a mayday. A towboat from Cape Cod intercepted Fabris’ calls for help and hastened to his location. The captain asked if Fabris had money for a tow. When the old Italian said yes, the towboat captain proceeded to tow him back to his home port of Falmouth. So at just fifteen hundred feet from Nantucket, Fabris was dragged thirty miles away to Cape Cod. When they arrived at the dock, as if to sprinkle salt in the wound, the towboat operator handed him a bill for $6,800.

Local Cape Codders didn’t know what to make of Fabris when he first arrived in Falmouth. His story quickly circulated around town until a group of Italian-Americans came to his aid, including a ninety-seven-year-old woman who taught Italian in the area. They helped set him up with lodgings and food, while reveling in his tales of survival. When the local yacht club heard of his plight, they set up a GoFundMe page to help buy him an airline ticket back to Italy. While appreciating the hospitality and new friendship on the Cape, Fabris insisted that his journey wasn’t over. He still needed to reach Nantucket to deliver the tiny whale statue that he had schlepped across the Atlantic. His newfound friends in Falmouth got him on the ferry and sent him off to the island.

Local Cape Codders didn’t know what to make of Fabris when he first arrived in Falmouth. His story quickly circulated around town until a group of Italian-Americans came to his aid, including a ninety-seven-year-old woman who taught Italian in the area. They helped set him up with lodgings and food, while reveling in his tales of survival. When the local yacht club heard of his plight, they set up a GoFundMe page to help buy him an airline ticket back to Italy. While appreciating the hospitality and new friendship on the Cape, Fabris insisted that his journey wasn’t over. He still needed to reach Nantucket to deliver the tiny whale statue that he had schlepped across the Atlantic. His newfound friends in Falmouth got him on the ferry and sent him off to the island.

When Lydia Sussek encountered Fabris at the Steamship ticket counter that late June afternoon, he had just left the Whaling Museum where he had attempted to donate the statue. Newspapers later erroneously reported that Fabris had been turned away by the Whaling Museum when they couldn’t understand him. However, museum executive director James Russell said that Fabris had in fact been given a private tour while they tried to figure out how to handle his donated work of art. Fabris later confirmed this account and wrote a letter to the publications insisting that they run a retraction.

Over the course of their ferry ride together, Sussek and Fabris formed a quick friendship. Although not Italian by blood, Sussek studied extensively in Italy, had mastered the language and spends a significant amount of time there each year. The two also connected over sailing, which Sussek and her husband had been doing for years on the island. After their impromptu meeting, Sussek arranged to bring Fabris back to the island a week later. He had suffered an eye injury during his voyage, so Sussek took him to see Dr. Mike Ruby to get examined. She also served as his translator on several subsequent trips to the Whaling Museum, where he met with Russell and ultimately donated the statue. After a full day on the island, the two sat at Cru restaurant enjoying lobster rolls in the sun while Fabris recounted his story, which has since become international news running in everything from The Wall Street Journal to the London Times.

Over the course of their ferry ride together, Sussek and Fabris formed a quick friendship. Although not Italian by blood, Sussek studied extensively in Italy, had mastered the language and spends a significant amount of time there each year. The two also connected over sailing, which Sussek and her husband had been doing for years on the island. After their impromptu meeting, Sussek arranged to bring Fabris back to the island a week later. He had suffered an eye injury during his voyage, so Sussek took him to see Dr. Mike Ruby to get examined. She also served as his translator on several subsequent trips to the Whaling Museum, where he met with Russell and ultimately donated the statue. After a full day on the island, the two sat at Cru restaurant enjoying lobster rolls in the sun while Fabris recounted his story, which has since become international news running in everything from The Wall Street Journal to the London Times.

“He loves it here,” Sussek translated for Fabris. “He’s made so many friends.” Still the old Venetian was eager to return home to reunite with his family, hopefully in time to celebrate his seventy-ninth birthday. Just before leaving, he sold his sailboat and donated the proceeds to the Whaling Museum. When asked what inspired him to set sail across the Atlantic at the age of seventy-seven, Fabris tacks between the symbolism he found in Moby-Dick and his own search for personal enlightenment. He’s still processing the full takeaways of his high-seas adventures, which he plans on committing to the pages of a memoir after he returns home. One thing is for certain: Vittorio Fabris is living proof that you’re never too old for a new adventure.