Rollicking tales of rum-running, bootlegging, and legendary Nantucket parties

You don’t need a Breathalyzer to prove that alcohol and Nantucket go together like gin and tonic. Just ask historian Frances Ruley Karttunen. “From the moment the English settlersset foot on Nantucket, alcohol was a problem for everyone,” Karttunen wrote in her intoxicating book, Law and Disorder on Nantucket. “In fact, for Tristram Coffin, undisputed leader of the investment group that acquired Nantucket from Thomas Mayhew in 1659, it was a problem even before he and his family shoved off from the mainland.” As it turned out, Coffin’s wife, Dionis, was something of a brewmaster back in Boston. When Puritan authorities found her brewing beer beyond the legal limit, Coffin and his family set sail for Nantucket. Alas, the island’s fondness for the drink traces back to its very founding.

Even during the country’s most sobering times — Prohibition — Nantucket held strong to its strong drink. Of the forty-six states to ratify the 18th Amendment, banning the sale and distribution of alcohol, Massachusetts was among the first. Within the Bay State, however, Nantucket was one of the very last holdouts. As historian Douglas K. Burch indicated in his article “90 Proof” published by the Nantucket Historical Association in 1993, “A contemporary commentator summed up the situation: ‘Nantucket is a dry town and will continue to vote dry just so long as its citizens are sober enough to stagger to the polls.’”

Just as today, Nantucket in the 1920s depended on tourism for its very survival. When the last of the whaling ships left port in 1896 never to return, beer barrels replaced oil barrels. Nightclubs and dance halls popped up around the island as city slickers fled the mugginess of New York and Boston with their luggage brimming with alcohol. As Burch described, “A typical tale concerns a spanking new Hudson touring car that labored off the boat one summer afternoon in 1927 and made it almost to the corner of Broad and Federal streets before its rear axle collapsed under the weight of its cargo of twenty-three cases of wine and whiskey.”

As photos of police pouring alcohol into sewer drains spilled out in national newspapers, a spirit of defiance brewed on Nantucket. “There was one event of national significance that seemed to me to have more impact on ‘Sconset life than perhaps the introduction of the automobile: Prohibition,” remembered Alice Beers to the Nantucket Historical Association in 1986. “While I have no clear recollection of much drinking before World War I, it seemed to me that defiance of the foolish law during and after the war became the fashion.” She added, “The cocktail assumed importance. Friends from Pennsylvania were popular because they could get ‘Apple-Jack’ — which, if gin was not available made a good drink. The afternoon cocktail party began to take over as the preferred form of entertainment. And as night follows day, the hip pocket flask and the reckless driver appeared as an inevitable phenomena.”

As photos of police pouring alcohol into sewer drains spilled out in national newspapers, a spirit of defiance brewed on Nantucket. “There was one event of national significance that seemed to me to have more impact on ‘Sconset life than perhaps the introduction of the automobile: Prohibition,” remembered Alice Beers to the Nantucket Historical Association in 1986. “While I have no clear recollection of much drinking before World War I, it seemed to me that defiance of the foolish law during and after the war became the fashion.” She added, “The cocktail assumed importance. Friends from Pennsylvania were popular because they could get ‘Apple-Jack’ — which, if gin was not available made a good drink. The afternoon cocktail party began to take over as the preferred form of entertainment. And as night follows day, the hip pocket flask and the reckless driver appeared as an inevitable phenomena.”

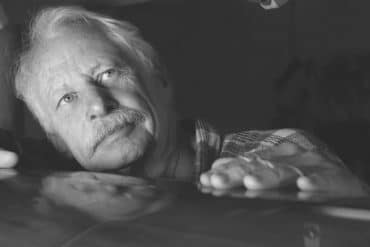

To keep the party rolling when their own supplies ran dry, Nantucketers relied on swashbuckling rumrunners to navigate the shallows and outsmart the Coast Guard’s so-called “Dry Navy.” “We had plenty of bootleggers around Nantucket, but no real rumrunners, only [my father],” claims ninety-seven-year-old Nantucket na- tive Phil Grant, today. “He had a big boat. A big boat. She drew twelve or fourteen feet. She had a false bottom. The name of it was the Maryland. She was 92-foot long, I think, and had a crew of five.”

A former Navy man in World War I, Peter Grant returned to his native Nantucket and discovered that his seamanship could be much more profitable running whiskey rather than fishing lines. Working for a gang in Connecticut, Grant sailed up to the Canadian islands Saint Pierre and Miquelon where he’d pick up barrels of Canadian whiskey to be stowed in the Maryland’s false bottom. He successfully made the voyages for six or seven years back and forth from Canada to Connecticut until the Nantucket Coast Guard finally wised up. When they started measuring the Maryland for depth, the Coast Guard quickly discovered her false bottom. “He got caught three times,” remembered Phil Grant. “The last time he got caught, he had to go to jail here on Nantucket. He spent thirty days in jail. He learned the laundry trade during those thirty days.”

Nantucket’s geographic location made it ideal for rumrunners. After 1924, the Dry Navy could only patrol within a twelve-mile line of demarcation, beyond which giant rum-running mother ships enjoyed lawless, international waters. The stretch of water southeast of Nantucket became part of what was known as Rum Row. Occasionally, local Nantucketers would get lucky when one of the large mother ships would run aground and be forced to jettison their boozy booty overboard before the authorities arrived. The biggest score came the day after Christmas in 1924 when the Waldo L Steam, ran aground off the west side of Nantucket. The Life Saving Crew based on Muskeget Island raced out to their rescue, saving the entire crew along with 2,295 cases of whiskey.

Nantucket’s geographic location made it ideal for rumrunners. After 1924, the Dry Navy could only patrol within a twelve-mile line of demarcation, beyond which giant rum-running mother ships enjoyed lawless, international waters. The stretch of water southeast of Nantucket became part of what was known as Rum Row. Occasionally, local Nantucketers would get lucky when one of the large mother ships would run aground and be forced to jettison their boozy booty overboard before the authorities arrived. The biggest score came the day after Christmas in 1924 when the Waldo L Steam, ran aground off the west side of Nantucket. The Life Saving Crew based on Muskeget Island raced out to their rescue, saving the entire crew along with 2,295 cases of whiskey.

As the Dry Navy clamped down on Rum Row, rum-running took off, quite literally. After the first seaplanes landed unannounced on Nantucket’s South Beach in April of 1918, the island slowly began turning out pilots of its own. One such aviator was a former radio operator at the Nantucket Coast Guard Station named Parker Gray. By 1927, Gray learned to fly, bought a couple planes, and eventually started Mayflower Airlines. Legend has it that in the face of the Prohibition, Gray stowed bottles of liquor destined for the island’s local merchants amongst his passengers’ luggage.

If they couldn’t smuggle their booze in by sea or by air, Nantucketers resorted to going inland and underground. Bootlegging was rampant. Just off Polpis Road, an elaborate distillery turned out high-grade moonshine under the cover of dirt and pine needles. Through a trap door hidden in the earth, bootleggers climbed down

into the hundred-square foot room where barrels of alcohol fermented away. When the FBI discovered the distillery in 1932, they declared it one of the most remarkable operations they’d unearthed in all their years of party pooping.

As we all know, when the 21st Amendment did away with the Prohibition in 1933, Nantucket went on to become a world-class food and drink destination. Look no further than the Nantucket Wine Festival this May to enjoy reverie at its finest. Of course, when you enjoy Nantucket, please do so responsibly.

A debt of gratitude goes out to Douglas K. Burch, Frances Ruley Karttunen, and the Nantucket Historical Association for their diligent research on this topic, from which the author drew for this article.

For those interested in learning more about the island’s Prohibition times as well as many other nefarious tales lurking in the dark corners of Nantucket history, pick up a copy of Frances Ruley Karttunen’s 2007 book, Law and Disorder in Old Nantucket, available at Mitchell’s Book Corner.